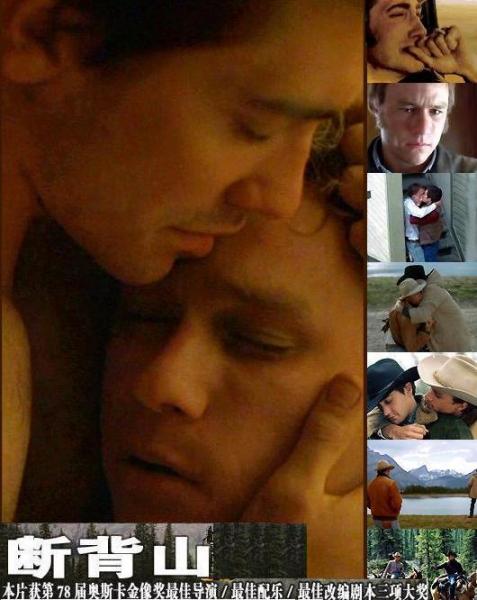

Brokeback mountain

by:E. Annie Proulx

Ennis Del Mar wakes before five, wind rocking the trailer, hissing in around the aluminum door and window frames. The shirts hanging on a nail shudder slightly in the draft. He gets up, scratching the grey wedge of belly and pubic hair, shuffles to the gas burner, pours leftover coffee in a chipped enamel pan; the flame swathes it in blue. He turns on the tap and urinates in the sink, pulls on his shirt and jeans, his worn boots, stamping the heels against the floor to get them full on. The wind booms down the curved length of the trailer and under its roaring passage he can hear the scratching of fine gravel and sand. It could be bad on the highway with the horse trailer. He has to be packed and away from the place that morning. Again the ranch is on the market and they've shipped out the last of the horses, paid everybody off the day before, the owner saying, "Give em to the real estate shark, I'm out a here," dropping the keys in Ennis's hand. He might have to stay with his married daughter until he picks up another job, yet he is suffused with a sense of pleasure because Jack Twist was in his dream.

The stale coffee is boiling up but he catches it before it goes over the side, pours it into a stained cup and blows on the black liquid, lets a panel of the dream slide forward. If he does not force his attention on it, it might stoke the day, rewarm that old, cold time on the mountain when they owned the world and nothing seemed wrong. The wind strikes the trailer like a load of dirt coming off a dump truck, eases, dies, leaves a temporary silence.

They were raised on small, poor ranches in opposite corners of the state, Jack Twist in Lightning Flat up on the Montana border, Ennis del Mar from around Sage, near the Utah line, both high school dropout country boys with no prospects, brought up to hard work and privation, both rough-mannered, rough-spoken, inured to the stoic life. Ennis, reared by his older brother and sister after their parents drove off the only curve on Dead Horse Road leaving them twenty-four dollars in cash and a two-mortgage ranch, applied at age fourteen for a hardship license that let him make the hour-long trip from the ranch to the high school. The pickup was old, no heater, one windshield wiper and bad tires; when the transmission went there was no money to fix it. He had wanted to be a sophomore, felt the word carried a kind of distinction, but the truck broke down short of it, pitching him directly into ranch work.

In 1963 when he met Jack Twist, Ennis was engaged to Alma Beers. Both Jack and Ennis claimed to be saving money for a small spread; in Ennis's case that meant a tobacco can with two five-dollar bills inside. That spring, hungry for any job, each had signed up with Farm and Ranch Employment -- they came together on paper as herder and camp tender for the same sheep operation north of Signal. The summer range lay above the tree line on Forest Service land on Brokeback Mountain. It would be Jack Twist's second summer on the mountain, Ennis's first. Neither of them was twenty.

They shook hands in the choky little trailer office in front of a table littered with scribbled papers, a Bakelite ashtray brimming with stubs. The venetian blinds hung askew and admitted a triangle of white light, the shadow of the foreman's hand moving into it. Joe Aguirre, wavy hair the color of cigarette ash and parted down the middle, gave them his point of view.

"Forest Service got designated campsites on the allotments. Them camps can be a couple a miles from where we pasture the sheep. Bad predator loss, nobody near lookin after em at night. What I want, camp tender in the main camp where the Forest Service says, but the HERDER" -- pointing at Jack with a chop of his hand -- "pitch a pup tent on the q.t. with the sheep, out a sight, and he's goin a SLEEP there. Eat supper, breakfast in camp, but SLEEP WITH THE SHEEP, hunderd percent, NO FIRE, don't leave NO SIGN. Roll up that tent every mornin case Forest Service snoops around. Got the dogs, your .30-.30, sleep there. Last summer had goddamn near twenty-five percent loss. I don't want that again. YOU," he said to Ennis, taking in the ragged hair, the big nicked hands, the jeans torn, button-gaping shirt, "Fridays twelve noon be down at the bridge with your next week list and mules. Somebody with supplies'll be there in a pickup." He didn't ask if Ennis had a watch but took a cheap round ticker on a braided cord from a box on a high shelf, wound and set it, tossed it to him as if he weren't worth the reach. "TOMORROW MORNIN we'll truck you up the jump-off." Pair of deuces going nowhere.

They found a bar and drank beer through the afternoon, Jack telling Ennis about a lightning storm on the mountain the year before that killed forty-two sheep, the peculiar stink of them and the way they bloated, the need for plenty of whiskey up there. He had shot an eagle, he said, turned his head to show the tail feather in his hatband. At first glance Jack seemed fair enough with his curly hair and quick laugh, but for a small man he carried some weight in the haunch and his smile disclosed buckteeth, not pronounced enough to let him eat popcorn out of the neck of a jug, but noticeable. He was infatuated with the rodeo life and fastened his belt with a minor bull-riding buckle, but his boots were worn to the quick, holed beyond repair and he was crazy to be somewhere, anywhere else than Lightning Flat.

Ennis, high-arched nose and narrow face, was scruffy and a little cave-chested, balanced a small torso on long, caliper legs, possessed a muscular and supple body made for the horse and for fighting. His reflexes were uncommonly quick and he was farsighted enough to dislike reading anything except Hamley's saddle catalog.

The sheep trucks and horse trailers unloaded at the trailhead and a bandy-legged Basque showed Ennis how to pack the mules, two packs and a riding load on each animal ring-lashed with double diamonds and secured with half hitches, telling him, "Don't never order soup. Them boxes a soup are real bad to pack." Three puppies belonging to one of the blue heelers went in a pack basket, the runt inside Jack's coat, for he loved a little dog. Ennis picked out a big chestnut called Cigar Butt to ride, Jack a bay mare who turned out to have a low startle point. The string of spare horses included a mouse-colored grullo whose looks Ennis liked. Ennis and Jack, the dogs, horses and mules, a thousand ewes and their lambs flowed up the trail like dirty water through the timber and out above the tree line into the great flowery Meadows and the coursing, endless wind.

They got the big tent up on the Forest Service's platform, the kitchen and grub boxes secured. Both slept in camp that first night, Jack already bitching about Joe Aguirre's sleep-with-the-sheep-and-no-fire order, though he saddled the bay mare in the dark morning without saying much. Dawn came glassy orange, stained from below by a gelatinous band of pale green. The sooty bulk of the mountain paled slowly until it was the same color as the smoke from Ennis's breakfast fire. The cold air sweetened, banded pebbles and crumbs of soil cast sudden pencil-long shadows and the rearing lodgepole pines below them massed in slabs of somber malachite.

During the day Ennis looked across a great gulf and sometimes saw Jack, a small dot moving across a high meadow as an insect moves across a tablecloth; Jack, in his dark camp, saw Ennis as night fire, a red spark on the huge black mass of mountain.

Jack came lagging in late one afternoon, drank his two bottles of beer cooled in a wet sack on the shady side of the tent, ate two bowls of stew, four of Ennis's stone biscuits, a can of peaches, rolled a smoke, watched the sun drop.

"I'm commutin four hours a day," he said morosely. "Come in for breakfast, go back to the sheep, evenin get em bedded down, come in for supper, go back to the sheep, spend half the night jumpin up and checkin for coyotes. By rights I should be spendin the night here. Aguirre got no right a make me do this."

"You want a switch?" said Ennis. "I wouldn't mind herdin. I wouldn't mind sleepin out there."

"That ain't the point. Point is, we both should be in this camp. And that goddamn pup tent smells like cat piss or worse."

"Wouldn't mind bein out there."

"Tell you what, you got a get up a dozen times in the night out there over them coyotes. Happy to switch but give you warnin I can't cook worth a sh*t. Pretty good with a can opener."

"Can't be no worse than me, then. Sure, I wouldn't mind a do it."

They fended off the night for an hour with the yellow kerosene lamp and around ten Ennis rode Cigar Butt, a good night horse, through the glimmering frost back to the sheep, carrying leftover biscuits, a jar of jam and a jar of coffee with him for the next day saying he'd save a trip, stay out until supper.

"Shot a coyote just first light," he told Jack the next evening, sloshing his face with hot water, lathering up soap and hoping his razor had some cut left in it, while Jack peeled potatoes. "Big son of a bitch. Balls on him size a apples. I bet he'd took a few lambs. Looked like he could a eat a camel. You want some a this hot water? There's plenty."

"It's all yours."

"Well, I'm goin a warsh everthing I can reach," he said, pulling off his boots and jeans (no drawers, no socks, Jack noticed), slopping the green washcloth around until the fire spat.

They had a high-time supper by the fire, a can of beans each, fried potatoes and a quart of whiskey on shares, sat with their backs against a log, boot soles and copper jeans rivets hot, swapping the bottle while the lavender sky emptied of color and the chill air drained down, drinking, smoking cigarettes, getting up every now and then to piss, firelight throwing a sparkle in the arched stream, tossing sticks on the fire to keep the talk going, talking horses and rodeo, roughstock events, wrecks and injuries sustained, the submarine Thresher lost two months earlier with all hands and how it must have been in the last doomed minutes, dogs each had owned and known, the draft, Jack's home ranch where his father and mother held on, Ennis's family place folded years ago after his folks died, the older brother in Signal and a married sister in Casper. Jack said his father had been a pretty well known bullrider years back but kept his secrets to himself, never gave Jack a word of advice, never came once to see Jack ride, though he had put him on the woolies when he was a little kid. Ennis said the kind of riding that interested him lasted longer than eight seconds and had some point to it. Money's a good point, said Jack, and Ennis had to agree. They were respectful of each other's opinions, each glad to have a companion where none had been expected. Ennis, riding against the wind back to the sheep in the treacherous, drunken light, thought he'd never had such a good time, felt he could paw the white out of the moon.

The summer went on and they moved the herd to new pasture, shifted the camp; the distance between the sheep and the new camp was greater and the night ride longer. Ennis rode easy, sleeping with his eyes open, but the hours he was away from the sheep stretched out and out. Jack pulled a squalling burr out of the harmonica, flattened a little from a fall off the skittish bay mare, and Ennis had a good raspy voice; a few nights they mangled their way through some songs. Ennis knew the salty words to "Strawberry Roan." Jack tried a Carl Perkins song, bawling "what I say-ay-ay," but he favored a sad hymn, "Water-Walking Jesus," learned from his mother who believed in the Pentecost, that he sang at dirge slowness, setting off distant coyote yips.

"Too late to go out to them damn sheep," said Ennis, dizzy drunk on all fours one cold hour when the moon had notched past two. The meadow stones glowed white-green and a flinty wind worked over the meadow, scraped the fire low, then ruffled it into yellow silk sashes. "Got you a extra blanket I'll roll up out here and grab forty winks, ride out at first light."

"Freeze your ass off when that fire dies down. Better off sleepin in the tent."

"Doubt I'll feel nothin." But he staggered under canvas, pulled his boots off, snored on the ground cloth for a while, woke Jack with the clacking of his jaw.

"Jesus Christ, quit hammerin and get over here. Bedroll's big enough," said Jack in an irritable sleep-clogged voice. It was big enough, warm enough, and in a little while they deepened their intimacy considerably. Ennis ran full-throttle on all roads whether fence mending or money spending, and he wanted none of it when Jack seized his left hand and brought it to his erect cock. Ennis jerked his hand away as though he'd touched fire, got to his knees, unbuckled his belt, shoved his pants down, hauled Jack onto all fours and, with the help of the clear slick and a little spit, entered him, nothing he'd done before but no instruction manual needed. They went at it in silence except for a few sharp intakes of breath and Jack's choked "gun's goin off," then out, down, and asleep.

Ennis woke in red dawn with his pants around his knees, a top-grade headache, and Jack butted against him; without saying anything about it both knew how it would go for the rest of the summer, sheep be damned.

As it did go. They never talked about the sex, let it happen, at first only in the tent at night, then in the full daylight with the hot sun striking down, and at evening in the fire glow, quick, rough, laughing and snorting, no lack of noises, but saying not a goddamn word except once Ennis said, "I'm not no queer," and Jack jumped in with "Me neither. A one-shot thing. Nobody's business but ours." There were only the two of them on the mountain flying in the euphoric, bitter air, looking down on the hawk's back and the crawling lights of vehicles on the plain below, suspended above ordinary affairs and distant from tame ranch dogs barking in the dark hours. They believed themselves invisible, not knowing Joe Aguirre had watched them through his 10x42 binoculars for ten minutes one day, waiting until they'd buttoned up their jeans, waiting until Ennis rode back to the sheep, before bringing up the message that Jack's people had sent word that his uncle Harold was in the hospital with pneumonia and expected not to make it. Though he did, and Aguirre came up again to say so, fixing Jack with his bold stare, not bothering to dismount.

In August Ennis spent the whole night with Jack in the main camp and in a blowy hailstorm the sheep took off west and got among a herd in another allotment. There was a damn miserable time for five days, Ennis and a Chilean herder with no English trying to sort them out, the task almost impossible as the paint brands were worn and faint at this late season. Even when the numbers were right Ennis knew the sheep were mixed. In a disquieting way everything seemed mixed.

The first snow came early, on August thirteenth, piling up a foot, but was followed by a quick melt. The next week Joe Aguirre sent word to bring them down -- another, bigger storm was moving in from the Pacific -- and they packed in the game and moved off the mountain with the sheep, stones rolling at their heels, purple cloud crowding in from the west and the metal smell of coming snow pressing them on. The mountain boiled with demonic energy, glazed with flickering broken-cloud light, the wind combed the grass and drew from the damaged krummholz and slit rock a bestial drone. As they descended the slope Ennis felt he was in a slow-motion, but headlong, irreversible fall.

Joe Aguirre paid them, said little. He had looked at the milling sheep with a sour expression, said, "Some a these never went up there with you." The count was not what he'd hoped for either. Ranch stiffs never did much of a job.

"You goin a do this next summer?" said Jack to Ennis in the street, one leg already up in his green pickup. The wind was gusting hard and cold.

"Maybe not." A dust plume rose and hazed the air with fine grit and he squinted against it. "Like I said, Alma and me's gettin married in December. Try to get somethin on a ranch. You?" He looked away from Jack's jaw, bruised blue from the hard punch Ennis had thrown him on the last day.

"If nothin better comes along. Thought some about going back up to my daddy's place, give him a hand over the winter, then maybe head out for Texas in the spring. If the draft don't get me."

"Well, see you around, I guess." The wind tumbled an empty feed bag down the street until it fetched up under his truck.

"Right," said Jack, and they shook hands, hit each other on the shoulder, then there was forty feet of distance between them and nothing to do but drive away in opposite directions. Within a mile Ennis felt like someone was pulling his guts out hand over hand a yard at a time. He stopped at the side of the road and, in the whirling new snow, tried to puke but nothing came up. He felt about as bad as he ever had and it took a long time for the feeling to wear off.

In December Ennis married Alma Beers and had her pregnant by mid-January. He picked up a few short-lived ranch jobs, then settled in as a wrangler on the old Elwood Hi-Top place north of Lost Cabin in Washakie County. He was still working there in September when Alma Jr., as he called his daughter, was born and their bedroom was full of the smell of old blood and milk and baby sh*t, and the sounds were of squalling and sucking and Alma's sleepy groans, all reassuring of fecundity and life's continuance to one who worked with livestock.

When the Hi-Top folded they moved to a small apartment in Riverton up over a laundry. Ennis got on the highway crew, tolerating it but working weekends at the Rafter B in exchange for keeping his horses out there. The second girl was born and Alma wanted to stay in town near the clinic because the child had an asthmatic wheeze.

"Ennis, please, no more damn lonesome ranches for us," she said, sitting on his lap, wrapping her thin, freckled arms around him. "Let's get a place here in town?"

"I guess," said Ennis, slipping his hand up her blouse sleeve and stirring the silky armpit hair, then easing her down, fingers moving up her ribs to the jelly breast, over the round belly and knee and up into the wet gap all the way to the north pole or the equator depending which way you thought you were sailing, working at it until she shuddered and bucked against his hand and he rolled her over, did quickly what she hated. They stayed in the little apartment which he favored because it could be left at any time.

The fourth summer since Brokeback Mountain came on and in June Ennis had a general delivery letter from Jack Twist, the first sign of life in all that time.

Friend this letter is a long time over due. Hope you get it. Heard you was in Riverton. Im coming thru on the 24th, thought Id stop and buy you a beer Drop me a line if you can, say if your there.

The return address was Childress, Texas. Ennis wrote back, you bet, gave the Riverton address.

The day was hot and clear in the morning, but by noon the clouds had pushed up out of the west rolling a little sultry air before them. Ennis, wearing his best shirt, white with wide black stripes, didn't know what time Jack would get there and so had taken the day off, paced back and forth, looking down into a street pale with dust. Alma was saying something about taking his friend to the Knife & Fork for supper instead of cooking it was so hot, if they could get a baby-sitter, but Ennis said more likely he'd just go out with Jack and get drunk. Jack was not a restaurant type, he said, thinking of the dirty spoons sticking out of the cans of cold beans balanced on the log.

Late in the afternoon, thunder growling, that same old green pickup rolled in and he saw Jack get out of the truck, beat-up Resistol tilted back. A hot jolt scalded Ennis and he was out on the landing pulling the door closed behind him. Jack took the stairs two and two. They seized each other by the shoulders, hugged mightily, squeezing the breath out of each other, saying, son of a bitch, son of a bitch, then, and easily as the right key turns the lock tumblers, their mouths came together, and hard, Jack's big teeth bringing blood, his hat falling to the floor, stubble rasping, wet saliva welling, and the door opening and Alma looking out for a few seconds at Ennis's straining shoulders and shutting the door again and still they clinched, pressing chest and groin and thigh and leg together, treading on each other's toes until they pulled apart to breathe and Ennis, not big on endearments, said what he said to his horses and daughters, little darlin.

The door opened again a few inches and Alma stood in the narrow light.

What could he say? "Alma, this is Jack Twist, Jack, my wife Alma." His chest was heaving. He could smell Jack -- the intensely familiar odor of cigarettes, musky sweat and a faint sweetness like grass, and with it the rushing cold of the mountain. "Alma," he said, "Jack and me ain't seen each other in four years." As if it were a reason. He was glad the light was dim on the landing but did not turn away from her.

"Sure enough," said Alma in a low voice. She had seen what she had seen. Behind her in the room lightning lit the window like a white sheet waving and the baby cried.

"You got a kid?" said Jack. His shaking hand grazed Ennis's hand, electrical current snapped between them.

"Two little girls," Ennis said. "Alma Jr. and Francine. Love them to pieces." Alma's mouth twitched.

"I got a boy," said Jack. "Eight months old. Tell you what, I married a cute little old Texas girl down in Childress -- Lureen." From the vibration of the floorboard on which they both stood Ennis could feel how hard Jack was shaking.

"Alma," he said. "Jack and me is goin out and get a drink. Might not get back tonight, we get drinkin and talkin."

"Sure enough," Alma said, taking a dollar bill from her pocket. Ennis guessed she was going to ask him to get her a pack of cigarettes, bring him back sooner.

"Please to meet you," said Jack, trembling like a run-out horse.

"Ennis -- " said Alma in her misery voice, but that didn't slow him down on the stairs and he called back, "Alma, you want smokes there's some in the pocket a my blue shirt in the bedroom."

They went off in Jack's truck, bought a bottle of whiskey and within twenty minutes were in the Motel Siesta jouncing a bed. A few handfuls of hail rattled against the window followed by rain and slippery wind banging the unsecured door of the next room then and through the night.

The room stank of semen and smoke and sweat and whiskey, of old carpet and sour hay, saddle leather, sh*t and cheap soap. Ennis lay spread-eagled, spent and wet, breathing deep, still half tumescent, Jack blowing forceful cigarette clouds like whale spouts, and Jack said, "Christ, it got a be all that time a yours ahorseback makes it so goddamn good. We got to talk about this. Swear to god I didn't know we was goin a get into this again -- yeah, I did. Why I'm here. I f*ckin knew it. Redlined all the way, couldn't get here fast enough."

"I didn't know where in the hell you was," said Ennis. "Four years. I about give up on you. I figured you was sore about that punch."

"Friend," said Jack, "I was in Texas rodeoin. How I met Lureen. Look over on that chair."

On the back of the soiled orange chair he saw the shine of a buckle. "Bullridin?"

"Yeah. I made three f*ckin thousand dollars that year. f*ckin starved. Had to borrow everthing but a toothbrush from other guys. Drove grooves across Texas. Half the time under that cunt truck fixin it. Anyway, I didn't never think about losin. Lureen? There's some serious money there. Her old man's got it. Got this farm machinery business. Course he don't let her have none a the money, and he hates my f*ckin guts, so it's a hard go now but one a these days -- "

"Well, you're goin a go where you look. Army didn't get you?" The thunder sounded far to the east, moving from them in its red wreaths of light.

"They can't get no use out a me. Got some crushed vertebrates. And a stress fracture, the arm bone here, you know how bullridin you're always leverin it off your thigh? -- she gives a little ever time you do it. Even if you tape it good you break it a little goddamn bit at a time. Tell you what, hurts like a bitch afterwards. Had a busted leg. Busted in three places. Come off the bull and it was a big bull with a lot a drop, he got rid a me in about three flat and he come after me and he was sure faster. Lucky enough. Friend a mine got his oil checked with a horn dipstick and that was all she wrote. Bunch a other things, f*ckin busted ribs, sprains and pains, torn ligaments. See, it ain't like it was in my daddy's time. It's guys with money go to college, trained athaletes. You got a have some money to rodeo now. Lureen's old man wouldn't give me a dime if I dropped it, except one way. And I know enough about the game now so I see that I ain't never goin a be on the bubble. Other reasons. I'm gettin out while I still can walk."

Ennis pulled Jack's hand to his mouth, took a hit from the cigarette, exhaled. "Sure as hell seem in one piece to me. You know, I was sittin up here all that time tryin to figure out if I was -- ? I know I ain't. I mean here we both got wives and kids, right? I like doin it with women, yeah, but Jesus H., ain't nothin like this. I never had no thoughts a doin it with another guy except I sure wrang it out a hunderd times thinkin about you. You do it with other guys? Jack?"

"sh*t no," said Jack, who had been riding more than bulls, not rolling his own. "You know that. Old Brokeback got us good and it sure ain't over. We got a work out what the f*ck we're goin a do now."

"That summer," said Ennis. "When we split up after we got paid out I had gut cramps so bad I pulled over and tried to puke, thought I ate somethin bad at that place in Dubois. Took me about a year a figure out it was that I shouldn't a let you out a my sights. Too late then by a long, long while."

"Friend," said Jack. "We got us a f*ckin situation here. Got a figure out what to do."

"I doubt there's nothin now we can do," said Ennis. "What I'm sayin, Jack, I built a life up in them years. Love my little girls. Alma? It ain't her fault. You got your baby and wife, that place in Texas. You and me can't hardly be decent together if what happened back there" -- he jerked his head in the direction of the apartment -- "grabs on us like that. We do that in the wrong place we'll be dead. There's no reins on this one. It scares the piss out a me."

"Got to tell you, friend, maybe somebody seen us that summer. I was back there the next June, thinkin about goin back -- I didn't, lit out for Texas instead -- and Joe Aguirre's in the office and he says to me, he says, 'You boys found a way to make the time pass up there, didn't you,' and I give him a look but when I went out I seen he had a big-ass pair a binoculars hangin off his rearview." He neglected to add that the foreman had leaned back in his squeaky wooden tilt chair, said, Twist, you guys wasn't gettin paid to leave the dogs baby-sit the sheep while you stemmed the rose, and declined to rehire him. He went on, "Yeah, that little punch a yours surprised me. I never figured you to throw a dirty punch."

"I come up under my brother K.E., three years older'n me, slugged me silly ever day. Dad got tired a me come bawlin in the house and when I was about six he set me down and says, Ennis, you got a problem and you got a fix it or it's gonna be with you until you're ninety and K.E.'s ninety-three. Well, I says, he's bigger'n me. Dad says, you got a take him unawares, don't say nothin to him, make him feel some pain, get out fast and keep doin it until he takes the message. Nothin like hurtin somebody to make him hear good. So I did. I got him in the outhouse, jumped him on the stairs, come over to his pillow in the night while he was sleepin and pasted him damn good. Took about two days. Never had trouble with K.E. since. The lesson was, don't say nothin and get it over with quick." A telephone rang in the next room, rang on and on, stopped abruptly in mid-peal.

"You won't catch me again," said Jack. "Listen. I'm thinkin, tell you what, if you and me had a little ranch together, little cow and calf operation, your horses, it'd be some sweet life. Like I said, I'm gettin out a rodeo. I ain't no broke-dick rider but I don't got the bucks a ride out this slump I'm in and I don't got the bones a keep gettin wrecked. I got it figured, got this plan, Ennis, how we can do it, you and me. Lureen's old man, you bet he'd give me a bunch if I'd get lost. Already more or less said it -- "

"Whoa, whoa, whoa. It ain't goin a be that way. We can't. I'm stuck with what I got, caught in my own loop. Can't get out of it. Jack, I don't want a be like them guys you see around sometimes. And I don't want a be dead. There was these two old guys ranched together down home, Earl and Rich -- Dad would pass a remark when he seen them. They was a joke even though they was pretty tough old birds. I was what, nine years old and they found Earl dead in a irrigation ditch. They'd took a tire iron to him, spurred him up, drug him around by his dick until it pulled off, just bloody pulp. What the tire iron done looked like pieces a burned tomatoes all over him, nose tore down from skiddin on gravel."

"You seen that?"

"Dad made sure I seen it. Took me to see it. Me and K.E. Dad laughed about it. Hell, for all I know he done the job. If he was alive and was to put his head in that door right now you bet he'd go get his tire iron. Two guys livin together? No. All I can see is we get together once in a while way the hell out in the back a nowhere -- "

"How much is once in a while?" said Jack. "Once in a while ever four f*ckin years?"

"No," said Ennis, forbearing to ask whose fault that was. "I goddamn hate it that you're goin a drive away in the mornin and I'm goin back to work. But if you can't fix it you got a stand it," he said. "sh*t. I been lookin at people on the street. This happen a other people? What the hell do they do?"

"It don't happen in Wyomin and if it does I don't know what they do, maybe go to Denver," said Jack, sitting up, turning away from him, "and I don't give a flyin f*ck. Son of a bitch, Ennis, take a couple days off. Right now. Get us out a here. Throw your stuff in the back a my truck and let's get up in the mountains. Couple a days. Call Alma up and tell her you're goin. Come on, Ennis, you just shot my airplane out a the sky -- give me somethin a go on. This ain't no little thing that's happenin here."

The hollow ringing began again in the next room, and as if he were answering it, Ennis picked up the phone on the bedside table, dialed his own number.

A slow corrosion worked between Ennis and Alma, no real trouble, just widening water. She was working at a grocery store clerk job, saw she'd always have to work to keep ahead of the bills on what Ennis made. Alma asked Ennis to use rubbers because she dreaded another pregnancy. He said no to that, said he would be happy to leave her alone if she didn't want any more of his kids. Under her breath she said, "I'd have em if you'd support em." And under that, thought, anyway, what you like to do don't make too many babies.

Her resentment opened out a little every year: the embrace she had glimpsed, Ennis's fishing trips once or twice a year with Jack Twist and never a vacation with her and the girls, his disinclination to step out and have any fun, his yearning for low paid, long-houred ranch work, his propensity to roll to the wall and sleep as soon as he hit the bed, his failure to look for a decent permanent job with the county or the power company, put her in a long, slow dive and when Alma Jr. was nine and Francine seven she said, what am I doin hangin around with him, divorced Ennis and married the Riverton grocer.

Ennis went back to ranch work, hired on here and there, not getting much ahead but glad enough to be around stock again, free to drop things, quit if he had to, and go into the mountains at short notice. He had no serious hard feelings, just a vague sense of getting shortchanged, and showed it was all right by taking Thanksgiving dinner with Alma and her grocer and the kids, sitting between his girls and talking horses to them, telling jokes, trying not to be a sad daddy. After the pie Alma got him off in the kitchen, scraped the plates and said she worried about him and he ought to get married again. He saw she was pregnant, about four, five months, he guessed.

"Once burned," he said, leaning against the counter, feeling too big for the room.

"You still go fishin with that Jack Twist?"

"Some." He thought she'd take the pattern off the plate with the scraping.

"You know," she said, and from her tone he knew something was coming, "I used to wonder how come you never brought any trouts home. Always said you caught plenty. So one time I got your creel case open the night before you went on one a your little trips -- price tag still on it after five years -- and I tied a note on the end of the line. It said, hello Ennis, bring some fish home, love, Alma. And then you come back and said you'd caught a bunch a browns and ate them up. Remember? I looked in the case when I got a chance and there was my note still tied there and that line hadn't touched water in its life." As though the word "water" had called out its domestic cousin she twisted the faucet, sluiced the plates.

"That don't mean nothin."

"Don't lie, don't try to fool me, Ennis. I know what it means. Jack Twist? Jack Nasty. You and him -- "

She'd overstepped his line. He seized her wrist; tears sprang and rolled, a dish clattered.

"Shut up," he said. "Mind your own business. You don't know nothin about it."

"I'm goin a yell for Bill."

"You f*ckin go right ahead. Go on and f*ckin yell. I'll make him eat the f*ckin floor and you too." He gave another wrench that left her with a burning bracelet, shoved his hat on backwards and slammed out. He went to the Black and Blue Eagle bar that night, got drunk, had a short dirty fight and left. He didn't try to see his girls for a long time, figuring they would look him up when they got the sense and years to move out from Alma.

They were no longer young men with all of it before them. Jack had filled out through the shoulders and hams, Ennis stayed as lean as a clothes-pole, stepped around in worn boots, jeans and shirts summer and winter, added a canvas coat in cold weather. A benign growth appeared on his eyelid and gave it a drooping appearance, a broken nose healed crooked.

Years on years they worked their way through the high meadows and mountain drainages, horse-packing into the Big Horns, Medicine Bows, south end of the Gallatins, Absarokas, Granites, Owl Creeks, the Bridger-Teton Range, the Freezeouts and the Shirleys, Ferrises and the Rattlesnakes, Salt River Range, into the Wind Rivers over and again, the Sierra Madres, Gros Ventres, the Washakies, Laramies, but never returning to Brokeback.

Down in Texas Jack's father-in-law died and Lureen, who inherited the farm equipment business, showed a skill for management and hard deals. Jack found himself with a vague managerial title, traveling to stock and agricultural machinery shows. He had some money now and found ways to spend it on his buying trips. A little Texas accent flavored his sentences, "cow" twisted into "kyow" and "wife" coming out as "waf." He'd had his front teeth filed down and capped, said he'd felt no pain, and to finish the job grew a heavy mustache.

In May of 1983 they spent a few cold days at a series of little icebound, no-name high lakes, then worked across into the Hail Strew River drainage.

Going up, the day was fine but the trail deep-drifted and slopping wet at the margins. They left it to wind through a slashy cut, leading the horses through brittle branchwood, Jack, the same eagle feather in his old hat, lifting his head in the heated noon to take the air scented with resinous lodgepole, the dry needle duff and hot rock, bitter juniper crushed beneath the horses' hooves. Ennis, weather-eyed, looked west for the heated cumulus that might come up on such a day but the boneless blue was so deep, said Jack, that he might drown looking up.

Around three they swung through a narrow pass to a southeast slope where the strong spring sun had had a chance to work, dropped down to the trail again which lay snowless below them. They could hear the river muttering and making a distant train sound a long way off. Twenty minutes on they surprised a black bear on the bank above them rolling a log over for grubs and Jack's horse shied and reared, Jack saying "Wo! Wo!" and Ennis's bay dancing and snorting but holding. Jack reached for the .30-.06 but there was no need; the startled bear galloped into the trees with the lumpish gait that made it seem it was falling apart.

The tea-colored river ran fast with snowmelt, a scarf of bubbles at every high rock, pools and setbacks streaming. The ochre-branched willows swayed stiffly, pollened catkins like yellow thumbprints. The horses drank and Jack dismounted, scooped icy water up in his hand, crystalline drops falling from his fingers, his mouth and chin glistening with wet.

"Get beaver fever doin that," said Ennis, then, "Good enough place," looking at the level bench above the river, two or three fire-rings from old hunting camps. A sloping meadow rose behind the bench, protected by a stand of lodgepole. There was plenty of dry wood. They set up camp without saying much, picketed the horses in the meadow. Jack broke the seal on a bottle of whiskey, took a long, hot swallow, exhaled forcefully, said, "That's one a the two things I need right now," capped and tossed it to Ennis.

On the third morning there were the clouds Ennis had expected, a grey racer out of the west, a bar of darkness driving wind before it and small flakes. It faded after an hour into tender spring snow that heaped wet and heavy. By nightfall it turned colder. Jack and Ennis passed a joint back and forth, the fire burning late, Jack restless and bitching about the cold, poking the flames with a stick, twisting the dial of the transistor radio until the batteries died.

Ennis said he'd been putting the blocks to a woman who worked part-time at the Wolf Ears bar in Signal where he was working now for Stoutamire's cow and calf outfit, but it wasn't going anywhere and she had some problems he didn't want. Jack said he'd had a thing going with the wife of a rancher down the road in Childress and for the last few months he'd slank around expecting to get shot by Lureen or the husband, one. Ennis laughed a little and said he probably deserved it. Jack said he was doing all right but he missed Ennis bad enough sometimes to make him whip babies.

The horses nickered in the darkness beyond the fire's circle of light. Ennis put his arm around Jack, pulled him close, said he saw his girls about once a month, Alma Jr. a shy seventeen-year-old with his beanpole length, Francine a little live wire. Jack slid his cold hand between Ennis's legs, said he was worried about his boy who was, no doubt about it, dyslexic or something, couldn't get anything right, fifteen years old and couldn't hardly read, he could see it though goddamn Lureen wouldn't admit to it and pretended the kid was o.k., refused to get any bitchin kind a help about it. He didn't know what the f*ck the answer was. Lureen had the money and called the shots.

"I used a want a boy for a kid," said Ennis, undoing buttons, "but just got little girls."

"I didn't want none a either kind," said Jack. "But f*ck-all has worked the way I wanted. Nothin never come to my hand the right way." Without getting up he threw deadwood on the fire, the sparks flying up with their truths and lies, a few hot points of fire landing on their hands and faces, not for the first time, and they rolled down into the dirt. One thing never changed: the brilliant charge of their infrequent couplings was darkened by the sense of time flying, never enough time, never enough.

A day or two later in the trailhead parking lot, horses loaded into the trailer, Ennis was ready to head back to Signal, Jack up to Lightning Flat to see the old man. Ennis leaned into Jack's window, said what he'd been putting off the whole week, that likely he couldn't get away again until November after they'd shipped stock and before winter feeding started.

"November. What in hell happened a August? Tell you what, we said August, nine, ten days. Christ, Ennis! Whyn't you tell me this before? You had a f*ckin week to say some little word about it. And why's it we're always in the friggin cold weather? We ought a do somethin. We ought a go south. We ought a go to Mexico one day."

"Mexico? Jack, you know me. All the travelin I ever done is goin around the coffeepot lookin for the handle. And I'll be runnin the baler all August, that's what's the matter with August. Lighten up, Jack. We can hunt in November, kill a nice elk. Try if I can get Don Wroe's cabin again. We had a good time that year."

"You know, friend, this is a goddamn bitch of a unsatisfactory situation. You used a come away easy. It's like seein the pope now."

"Jack, I got a work. Them earlier days I used a quit the jobs. You got a wife with money, a good job. You forget how it is bein broke all the time. You ever hear a child support? I been payin out for years and got more to go. Let me tell you, I can't quit this one. And I can't get the time off. It was tough gettin this time -- some a them late heifers is still calvin. You don't leave then. You don't. Stoutamire is a hell-raiser and he raised hell about me takin the week. I don't blame him. He probly ain't got a night's sleep since I left. The trade-off was August. You got a better idea?"

"I did once." The tone was bitter and accusatory.

Ennis said nothing, straightened up slowly, rubbed at his forehead; a horse stamped inside the trailer. He walked to his truck, put his hand on the trailer, said something that only the horses could hear, turned and walked back at a deliberate pace.

"You been a Mexico, Jack?" Mexico was the place. He'd heard. He was cutting fence now, trespassing in the shoot-em zone.

"Hell yes, I been. Where's the f*ckin problem?" Braced for it all these years and here it came, late and unexpected.

"I got a say this to you one time, Jack, and I ain't foolin. What I don't know," said Ennis, "all them things I don't know could get you killed if I should come to know them."

"Try this one," said Jack, "and I'll say it just one time. Tell you what, we could a had a good life together, a f*ckin real good life. You wouldn't do it, Ennis, so what we got now is Brokeback Mountain. Everthing built on that. It's all we got, boy, f*ckin all, so I hope you know that if you don't never know the rest. Count the damn few times we been together in twenty years. Measure the f*ckin short leash you keep me on, then ask me about Mexico and then tell me you'll kill me for needin it and not hardly never gettin it. You got no f*ckin idea how bad it gets. I'm not you. I can't make it on a couple a high-altitude f*cks once or twice a year. You're too much for me, Ennis, you son of a whoreson bitch. I wish I knew how to quit you."

Like vast clouds of steam from thermal springs in winter the years of things unsaid and now unsayable -- admissions, declarations, shames, guilts, fears -- rose around them. Ennis stood as if heart-shot, face grey and deep-lined, grimacing, eyes screwed shut, fists clenched, legs caving, hit the ground on his knees.

"Jesus," said Jack. "Ennis?" But before he was out of the truck, trying to guess if it was heart attack or the overflow of an incendiary rage, Ennis was back on his feet and somehow, as a coat hanger is straightened to open a locked car and then bent again to its original shape, they torqued things almost to where they had been, for what they'd said was no news. Nothing ended, nothing begun, nothing resolved.

What Jack remembered and craved in a way he could neither help nor understand was the time that distant summer on Brokeback when Ennis had come up behind him and pulled him close, the silent embrace satisfying some shared and sexless hunger.

They had stood that way for a long time in front of the fire, its burning tossing ruddy chunks of light, the shadow of their bodies a single column against the rock. The minutes ticked by from the round watch in Ennis's pocket, from the sticks in the fire settling into coals. Stars bit through the wavy heat layers above the fire. Ennis's breath came slow and quiet, he hummed, rocked a little in the sparklight and Jack leaned against the steady heartbeat, the vibrations of the humming like faint electricity and, standing, he fell into sleep that was not sleep but something else drowsy and tranced until Ennis, dredging up a rusty but still useable phrase from the childhood time before his mother died, said, "Time to hit the hay, cowboy. I got a go. Come on, you're sleepin on your feet like a horse," and gave Jack a shake, a push, and went off in the darkness. Jack heard his spurs tremble as he mounted, the words "see you tomorrow," and the horse's shuddering snort, grind of hoof on stone.

Later, that dozy embrace solidified in his memory as the single moment of artless, charmed happiness in their separate and difficult lives. Nothing marred it, even the knowledge that Ennis would not then embrace him face to face because he did not want to see nor feel that it was Jack he held. And maybe, he thought, they'd never got much farther than that. Let be, let be.

Ennis didn't know about the accident for months until his postcard to Jack saying that November still looked like the first chance came back stamped DECEASED. He called Jack's number in Childress, something he had done only once before when Alma divorced him and Jack had misunderstood the reason for the call, had driven twelve hundred miles north for nothing. This would be all right, Jack would answer, had to answer. But he did not. It was Lureen and she said who? who is this? and when he told her again she said in a level voice yes, Jack was pumping up a flat on the truck out on a back road when the tire blew up. The bead was damaged somehow and the force of the explosion slammed the rim into his face, broke his nose and jaw and knocked him unconscious on his back. By the time someone came along he had drowned in his own blood.

No, he thought, they got him with the tire iron.

"Jack used to mention you," she said. "You're the fishing buddy or the hunting buddy, I know that. Would have let you know," she said, "but I wasn't sure about your name and address. Jack kept most a his friends' addresses in his head. It was a terrible thing. He was only thirty-nine years old."

The huge sadness of the northern plains rolled down on him. He didn't know which way it was, the tire iron or a real accident, blood choking down Jack's throat and nobody to turn him over. Under the wind drone he heard steel slamming off bone, the hollow chatter of a settling tire rim.

"He buried down there?" He wanted to curse her for letting Jack die on the dirt road.

The little Texas voice came slip-sliding down the wire. "We put a stone up. He use to say he wanted to be cremated, ashes scattered on Brokeback Mountain. I didn't know where that was. So he was cremated, like he wanted, and like I say, half his ashes was interred here, and the rest I sent up to his folks. I thought Brokeback Mountain was around where he grew up. But knowing Jack, it might be some pretend place where the bluebirds sing and there's a whiskey spring."

"We herded sheep on Brokeback one summer," said Ennis. He could hardly speak.

"Well, he said it was his place. I thought he meant to get drunk. Drink whiskey up there. He drank a lot."

"His folks still up in Lightnin Flat?"

"Oh yeah. They'll be there until they die. I never met them. They didn't come down for the funeral. You get in touch with them. I suppose they'd appreciate it if his wishes was carried out."

No doubt about it, she was polite but the little voice was cold as snow.

The road to Lightning Flat went through desolate country past a dozen abandoned ranches distributed over the plain at eight- and ten-mile intervals, houses sitting blank-eyed in the weeds, corral fences down. The mailbox read John C. Twist. The ranch was a meagre little place, leafy spurge taking over. The stock was too far distant for him to see their condition, only that they were black baldies. A porch stretched across the front of the tiny brown stucco house, four rooms, two down, two up.

Ennis sat at the kitchen table with Jack's father. Jack's mother, stout and careful in her movements as though recovering from an operation, said, "Want some coffee, don't you? Piece a cherry cake?"

"Thank you, ma'am, I'll take a cup a coffee but I can't eat no cake just now."

The old man sat silent, his hands folded on the plastic tablecloth, staring at Ennis with an angry, knowing expression. Ennis recognized in him a not uncommon type with the hard need to be the stud duck in the pond. He couldn't see much of Jack in either one of them, took a breath.

"I feel awful bad about Jack. Can't begin to say how bad I feel. I knew him a long time. I come by to tell you that if you want me to take his ashes up there on Brokeback like his wife says he wanted I'd be proud to."

There was a silence. Ennis cleared his throat but said nothing more.

The old man said, "Tell you what, I know where Brokeback Mountain is. He thought he was too goddamn special to be buried in the family plot."

Jack's mother ignored this, said, "He used a come home every year, even after he was married and down in Texas, and help his daddy on the ranch for a week fix the gates and mow and all. I kept his room like it was when he was a boy and I think he appreciated that. You are welcome to go up in his room if you want."

The old man spoke angrily. "I can't get no help out here. Jack used a say, 'Ennis del Mar,' he used a say, 'I'm goin a bring him up here one a these days and we'll lick this damn ranch into shape.' He had some half-baked idea the two a you was goin a move up here, build a log cabin and help me run this ranch and bring it up. Then, this spring he's got another one's goin a come up here with him and build a place and help run the ranch, some ranch neighbor a his from down in Texas. He's goin a split up with his wife and come back here. So he says. But like most a Jack's ideas it never come to pass."

So now he knew it had been the tire iron. He stood up, said, you bet he'd like to see Jack's room, recalled one of Jack's stories about this old man. Jack was dick-clipped and the old man was not; it bothered the son who had discovered the anatomical disconformity during a hard scene. He had been about three or four, he said, always late getting to the toilet, struggling with buttons, the seat, the height of the thing and often as not left the surroundings sprinkled down. The old man blew up about it and this one time worked into a crazy rage. "Christ, he licked the stuffin out a me, knocked me down on the bathroom floor, whipped me with his belt. I thought he was killin me. Then he says, 'You want a know what it's like with piss all over the place? I'll learn you,' and he pulls it out and lets go all over me, soaked me, then he throws a towel at me and makes me mop up the floor, take my clothes off and warsh them in the bathtub, warsh out the towel, I'm bawlin and blubberin. But while he was hosin me down I seen he had some extra material that I was missin. I seen they'd cut me different like you'd crop a ear or scorch a brand. No way to get it right with him after that."

The bedroom, at the top of a steep stair that had its own climbing rhythm, was tiny and hot, afternoon sun pounding through the west window, hitting the narrow boy's bed against the wall, an ink-stained desk and wooden chair, a b.b. gun in a hand-whittled rack over the bed. The window looked down on the gravel road stretching south and it occurred to him that for his growing-up years that was the only road Jack knew. An ancient magazine photograph of some dark-haired movie star was taped to the wall beside the bed, the skin tone gone magenta. He could hear Jack's mother downstairs running water, filling the kettle and setting it back on the stove, asking the old man a muffled question.

The closet was a shallow cavity with a wooden rod braced across, a faded cretonne curtain on a string closing it off from the rest of the room. In the closet hung two pairs of jeans crease-ironed and folded neatly over wire hangers, on the floor a pair of worn packer boots he thought he remembered. At the north end of the closet a tiny jog in the wall made a slight hiding place and here, stiff with long suspension from a nail, hung a shirt. He lifted it off the nail. Jack's old shirt from Brokeback days. The dried blood on the sleeve was his own blood, a gushing nosebleed on the last afternoon on the mountain when Jack, in their contortionistic grappling and wrestling, had slammed Ennis's nose hard with his knee. He had staunched the blood which was everywhere, all over both of them, with his shirtsleeve, but the staunching hadn't held because Ennis had suddenly swung from the deck and laid the ministering angel out in the wild columbine, wings folded.

The shirt seemed heavy until he saw there was another shirt inside it, the sleeves carefully worked down inside Jack's sleeves. It was his own plaid shirt, lost, he'd thought, long ago in some damn laundry, his dirty shirt, the pocket ripped, buttons missing, stolen by Jack and hidden here inside Jack's own shirt, the pair like two skins, one inside the other, two in one. He pressed his face into the fabric and breathed in slowly through his mouth and nose, hoping for the faintest smoke and mountain sage and salty sweet stink of Jack but there was no real scent, only the memory of it, the imagined power of Brokeback Mountain of which nothing was left but what he held in his hands.

In the end the stud duck refused to let Jack's ashes go. "Tell you what, we got a family plot and he's goin in it." Jack's mother stood at the table coring apples with a sharp, serrated instrument. "You come again," she said.

Bumping down the washboard road Ennis passed the country cemetery fenced with sagging sheep wire, a tiny fenced square on the welling prairie, a few graves bright with plastic flowers, and didn't want to know Jack was going in there, to be buried on the grieving plain.

A few weeks later on the Saturday he threw all Stoutamire's dirty horse blankets into the back of his pickup and took them down to the Quik Stop Car Wash to turn the high-pressure spray on them. When the wet clean blankets were stowed in the truck bed he stepped into Higgins's gift shop and busied himself with the postcard rack.

"Ennis, what are you lookin for rootin through them postcards?" said Linda Higgins, throwing a sopping brown coffee filter into the garbage can.

"Scene a Brokeback Mountain."

"Over in Fremont County?"

"No, north a here."

"I didn't order none a them. Let me get the order list. They got it I can get you a hunderd. I got a order some more cards anyway."

"One's enough," said Ennis.

When it came -- thirty cents -- he pinned it up in his trailer, brass-headed tack in each corner. Below it he drove a nail and on the nail he hung the wire hanger and the two old shirts suspended from it. He stepped back and looked at the ensemble through a few stinging tears.

"Jack, I swear -- " he said, though Jack had never asked him to swear anything and was himself not the swearing kind.

Around that time Jack began to appear in his dreams, Jack as he had first seen him, curly-headed and smiling and bucktoothed, talking about getting up off his pockets and into the control zone, but the can of beans with the spoon handle jutting out and balanced on the log was there as well, in a cartoon shape and lurid colors that gave the dreams a flavor of comic obscenity. The spoon handle was the kind that could be used as a tire iron. And he would wake sometimes in grief, sometimes with the old sense of joy and release; the pillow sometimes wet, sometimes the sheets.

There was some open space between what he knew and what he tried to believe, but nothing could be done about it, and if you can't fix it you've got to stand it.

埃尼斯?德?玛尔不到五点就醒了,风摇晃着拖车,嘶嘶作响地从铝制门窗缝儿钻进来,吹得挂在钉子上的衬衣微微抖动。他爬起来,挠了挠下体和阴毛,慢腾腾地走到煤气灶前,把上次喝剩的咖啡倒进缺了个口儿的搪瓷锅子里。蓝色的火焰登时裹住了锅子。他打开水龙头在小便槽里撒了泡尿,穿上衬衣牛仔裤和他那破靴子,用脚跟在地板上蹬了蹬把整个脚穿了进去。

风沿着拖车的轮廓呼啸着打转,他都能听到沙砾在风中发出刮擦声。在公路上开着辆破拖车赶路可真够糟糕的,但是今天早上他就必须打好包,离开此地。农场被卖掉了,最后一匹马也已经运走了,前天农场主就支付了所有人的工钱打发他们离开。他把钥匙扔给埃尼斯,说了句“农场交给房地产经纪吧,我走了”。看来,在找到下一份活儿之前,埃尼斯就只好跟他那已经嫁了人的闺女呆在一起了。但是他心里头美滋滋的,因为在梦里,他又见到了杰克。

咖啡沸了。没等溢出来他就提起了锅子,把它倒进一个脏兮兮的杯子里。他吹了吹这些黑色的液体,继续琢磨那个梦。稍不留神,那梦境就把他带回了以往的辰光,令他重温那些寒冷的山中岁月——那时候他们拥有整个世界,无忧无虑,随心所欲……

风还在吹打着拖车,那情形就像把一车泥土从运沙车上倾倒下来似的,由强到弱,继而留下片刻的寂静。

他们都生长在蒙大拿州犄角旮旯那种又小又穷的农场里,杰克来自州北部边境的赖特宁平原,埃尼斯则来自离犹他州边境不远的塞奇郡附近;两人都是高中没读完就辍学了,前途无望,注定将来得干重活、过穷日子;两人都举止粗鲁、满口脏话,习惯了节俭度日。埃尼斯是他哥哥和姐姐养大的。他们的父母在“鬼见愁”唯一的拐弯处翻了车,给他们留下了二十四块钱现金和一个被双重抵押的农场。埃尼斯十四岁的时候申请了执照,可以从农场长途跋涉去上高中了。他开的是一辆旧的小货车,没有取暖器,只有一个雨刷,轮胎也挺差劲儿;好不容易开到了,却又没钱修车了。他本来计划读到高二,觉得那样听上去体面。可是这辆货车破坏了他的计划,把他直接铲回农场干起了农活。

1963年遇到杰克时,埃尼斯已经和阿尔玛?比尔斯订了婚。两个男人都想攒点钱将来结婚时能办个小酒宴。对埃尼斯来说,这意味着香烟罐里得存上个10美元。那年春天,他们都急着找工作,于是双双和农场签了合同,一起到斯加纳北部牧羊。合同上两人签的分别是牧羊人和驻营者。夏日的山脉横亘在断背山林业局外面的林木线上,这是杰克在山上第二次过夏天,埃尼斯则是第一次。当时两人都还不满二十岁。

在一个小得令人窒息的活动拖车办公室里,他们站在一张铺满草稿纸的桌子前握了握手,桌上还搁着一只塞满烟头的树胶烟灰缸。活动百叶窗歪歪斜斜地挂着,一角白光从中漏进来,工头乔?安奎尔的手移到了白光中。乔留着一头中分的烟灰色波浪发,在给他俩面授机宜。

“林业局在山上有块儿指定的露营地,可营地离放羊的地方有好几英里。到了晚上就没人看着羊了,可给野兽吃了不少。所以,我是这么想的:你们中的一个人在林业局规定的地方照看营地,另一个人——”他用手指着杰克,“在羊群里支一个小帐篷,不要给人看到。早饭、晚饭在营地里吃,但是夜里要和羊睡在一起,绝对不许生火,也绝对不许擅离职守。每天早上把帐篷卷起来,以防林业局来巡查。带上狗,你就睡那儿。去年夏天,该死的,我们损失了近百分之二十五的羊。我可不想再发生这种事。你,” 他对埃尼斯说——后者留着一头乱发,一双大手伤痕累累,穿着破旧的牛仔裤和缺纽扣的衬衫——“每个星期五中午12点,你带上下周所需物品清单和你的骡子到桥上去。有人会开车把给养送来。”他没问埃尼斯带表了没,径直从高架上的盒子里取出一只系着辫子绳的廉价圆形怀表,转了转,上好发条,抛给了对方,手臂都懒得伸一伸:“明天早上我们开车送你们走。”

他们无处可去,找了家酒吧,喝了一下午啤酒,杰克告诉埃尼斯前年山上的一场雷雨死了四十二只羊,那股恶臭和肿胀的羊尸,得喝好多威士忌才能压得住。他还曾射下一只鹰,说着转过头去给埃尼斯看插在帽带上的尾羽。

乍一看,杰克长得很好看,一头卷发,笑声轻快活泼,对一个小个子来说腰粗了点,一笑就露出一口小龅牙,他的牙虽然没有长到足以让他能从茶壶颈里吃到爆米花,不过也够醒目的。他很迷恋牛仔生活,腰带上系了个小小的捕牛扣,靴子已经破得没法再补了。他发疯似地要到别处去,什么地方都可以,只要不用待在赖特宁平原。

埃尼斯,高鼻梁,瘦脸型,邋里邋遢的,胸部有点凹陷,上身短,腿又长又弯。他有一身适合骑马和打架的坚韧肌肉。反应敏捷,远视得很厉害,所以除了哈姆莱的马鞍目录,什么书都不爱看。

卡车和马车把羊群卸在路口,一个罗圈腿的巴斯克人教埃尼斯怎么往骡子身上装货,每个牲口背两个包裹和一副乘具——巴斯克人跟他说“千万别要汤,汤盒儿太难带了”——背篓里放着三只小狗,还有一只小狗崽子藏在杰克的上衣里,他喜欢小狗。埃尼斯挑了匹叫雪茄头的栗色马当坐骑,杰克则挑了匹红棕色母马——后来才发现它脾气火爆。剩下的马中还有一头鼠灰色的,看起来跟埃尼斯挺像。埃尼斯、杰克、狗、马、骡子走在前面,一千多只母羊和羊崽紧跟其后,就像一股浊流穿过树林,追逐着无处不在的山风,向上涌至那繁花盛开的草地上。

他们在林业局指定的地方支起了大帐篷,把锅灶和食盒固定好。第一天晚上他们都睡在帐篷里。杰克已经开始对乔让他和羊睡在一起并且不准生火的指令骂娘了。不过第二天早上,天还没亮,他还是一言不发地给他的母马上好了鞍。黎明时分,天边一片透明的橙黄色,下面点缀着一条凝胶般的淡绿色带子。黑黝黝的山色渐渐转淡,直到和埃尼斯做早饭时的炊烟浑然一色。凛冽的空气慢慢变暖,山峦突然间洒下了铅笔一样细长的影子,山下的黑松郁郁葱葱,好像一堆堆阴暗的孔雀石。

白天,埃尼斯朝山谷那边望过去,有时能看到杰克:一个小点在高原上移动,就好像一只昆虫爬过一块桌布;而晚上,杰克从他那漆黑一团的帐篷里望过去,埃尼斯就像是一簇夜火,一星绽放在大山深处的火花。

一天傍晚杰克拖着脚步回来了,他喝了晾在帐篷背阴处湿麻袋里的两瓶啤酒,吃了两碗炖肉,啃了四块埃尼斯的硬饼干和一罐桃子罐头,卷了根烟,看着太阳落下去。

“一天光换班就要在路上花上四小时。”他愁眉苦脸地说,“先回来吃早饭,然后回到羊群,傍晚伺候它们睡下,再回来吃晚饭,又回到羊群,大半个晚上都得防备着有没有狼来……我有权晚上睡在这儿,乔凭什么不许我留下。”

“你想换一下吗?”埃尼斯说,“我不介意去放羊。也不介意跟羊睡一起。”

“不是这么回事。我的意思是,咱俩都应该睡在这里。那个该死的小帐篷就跟猫尿一样臭,比猫尿还臭。”“我去看羊好了,无所谓的。”

“跟你说,晚上你可得起来十多次,防狼。你跟我换我很乐意,不过给你提个醒,我做饭很烂。用罐头开瓶器倒是很熟练。”“肯定不会比我烂的。我真不介意。”

晚上,他们在发着黄光的煤油灯下了呆了一小时,十点左右埃尼斯骑着雪茄头走了。雪茄头真是匹夜行的好马,披着冰霜的寒光就回到了羊群。埃尼斯带走了剩下的饼干,一罐果酱,以及一罐咖啡,他说明天他要在外面待到吃晚饭的时候,省得早晨还得往回跑一趟。

“天刚亮就打了匹狼,”第二天傍晚,杰克削土豆的时候埃尼斯对他说。他用热水泼着脸,又往脸上抹肥皂,好让他的刮胡刀更好使。“狗娘养的。睾丸大得跟苹果似的。我打赌它一准儿吃了不少羊崽——看上去都能吞下一匹骆驼。你要点热水吗?还有很多。”

“都是给你的。”“哦,那我可好好洗洗了。”说着,他脱下靴子和牛仔裤(没穿内裤,没穿袜子,杰克注意到),挥舞着那条绿色的毛巾,把火苗扇得又高又旺。

他们围着篝火吃了一顿非常愉快的晚餐。一人一罐豆子,配上炸土豆,还分享了一夸脱威士忌。两人背靠一根圆木坐着,靴子底和牛仔裤的铜扣被篝火烘得暖融融的,酒瓶在他们手里交替传递。天空中的淡紫色渐渐退却,冷气消散。他们喝着酒,抽着烟,时不时地起来撒泡尿,火光在弯弯曲曲的小溪上投下火星。他们一边往火上添柴,一边聊天:聊马仔牛仔们的表演;聊股市行情;聊彼此受过的伤;聊两个月前长尾鲨潜水艇失事的细节,包括对失事前那可怕的最后几分钟的揣测;聊他们养过的和知道的狗;聊牲口;聊杰克家由他爹妈打理的农场;埃尼斯说,父母双亡后他家就散了,他哥在西格诺,姐姐则嫁到了卡斯帕尔;杰克说他爹从前会驯牛,但他一直没有声张,也从来不指点杰克,从来不看杰克骑牛,尽管小时候曾把杰克放到羊背上;埃尼斯说他也对驯牛感兴趣,能骑八秒多,还颇有点心得;杰克说钱是个好东西,埃尼斯表示同意……他们尊重对方的意见,彼此都很高兴在这种鸟不生蛋的地方能有这么个伴儿。埃尼斯骑着马,踏着迷蒙的夜色醉醺醺地驰回了羊群,心里觉得自个儿从来没有这么快乐过,快乐得都能伸手抓下一片白月光。

夏天还在继续。他们把羊群赶到了一片新的草地上,同时转移了营地;羊群和营地的距离更大了,晚上骑马回营地所用的时间也更长了。埃尼斯骑马的时候很潇洒,睡觉的时候都睁着眼,可他离开羊群的时间却越拉越长。杰克把他的口琴吹得嗡嗡响——母马发脾气的时候,口琴曾经给摔到地上过,不那么光亮了。埃尼斯有一副高亢的好嗓子。有几个晚上他们在一起乱唱一气。埃尼斯知道“草莓枣红马”这类歪歪歌词,杰克则扯着嗓子唱“what I say-ay-ay”(我所说的……),那是卡尔?帕金斯的歌。但他最喜欢的是一首忧伤的圣歌:“耶稣基督行于水上”。是跟他那位笃信圣灵降临节的母亲学的。他像唱挽歌一样缓缓地唱着,引得远处狼嚎四起。

“太晚了,不想管那些该死的羊了”埃尼斯说道,醉醺醺地仰面躺着。正是寒冷时分,从月亮的位置看已过了两点钟。草地上的石头泛着白绿色幽光,冷风呼啸而过,把火苗压得很低,就像给火焰镶上了一条黄色的花边儿。“给我一条多余的毯子,我在外面一卷就可以睡,打上四十个盹,天就亮了。”“等火灭了非把你的屁股冻掉不可。还是睡帐篷吧。”

“没事。”他摇摇晃晃地钻出了了帆布帐篷,扯掉靴子,刚在铺在地下的毯子上打了一小会儿呼噜,就上牙嗑下牙地叫醒了杰克。

“天啊,不要哆嗦了,过来,被窝大着呢。” 杰克睡意朦胧,不耐烦地说到。被窝很大,也很温暖,不一会儿他们便越过雷池,变得非常亲密了。埃尼斯本来还胡思乱想着修栅栏和钱的事儿,当杰克抓住他的左手移到自己勃起的阴茎上时,他的大脑顿时一片空白。他像被火烫了似的把手抽了回来,跪起身,解开皮带,拉下裤子,把杰克仰面翻过来,在透明的液体和一点点唾液的帮助下,闯了进去,他从来没这么做过,不过这也并不需要什么说明书。他们一声不吭地进行着,间或发出几声急促的喘息。杰克紧绷的“熗”发射了,然后埃尼斯退出来,躺下,坠入梦乡。

埃尼斯在黎明的满天红光中醒来,裤子还褪在膝盖上,头疼得厉害,杰克在后面顶着他,两人什么都没说,彼此都心知肚明接下来的日子这事还会继续下去。让羊去见鬼吧!

这种事的确仍在继续。他们从来不“谈”性,而是用“做”的。一开始还只是深夜时候在帐篷里做,后来在大白天热辣辣的太阳下面也做,又或者在傍晚的火光中做。又快又粗暴,边笑边喘息,什么动静儿都有,就是不说话。只有一次,埃尼斯说:“我可不是玻璃。”杰克立马接口:“我也不是。就这一回,就你跟我,和别人那种事儿不一样。”山上只有他俩,在轻快而苦涩的空气里狂欢。鸟瞰山脚,山下平原上的车灯闪烁着晃动。他们远离尘嚣,唯有从远处夜色中的农场里,传来隐隐狗吠……他俩以为没人能看见他们。可他们不知道,有一天,乔?安奎尔用他那10*42倍距的双目望远镜足足看了他们十分钟。一直等到他俩穿好牛仔裤,扣好扣子,埃尼斯骑马驰回羊群,他才现身。乔告诉杰克,他家人带话来,说杰克的叔叔哈罗德得肺炎住院了,估计就要挺不过去了。后来叔叔安然无恙,乔又上来报信,两眼死死地盯着杰克,连马都没下。

八月份,埃尼斯整夜和杰克呆在主营里。一场狂风挟裹着冰雹袭来,羊群往西跑到了另一片草场,和那里的羊混在了一起。真倒霉,他们整整忙活了五天。埃尼斯跟一个不会说英语的智利牧羊人试着把羊们分开来,但这几乎不可能的,因为到了这个季节,羊身上的那些油漆标记都已经看不清了。到最后,数量是弄对了,但埃尼斯知道,羊还是混了。在这种惶惶不安的局面下,一切似乎都乱了套。

八月十三日,山里的第一场雪早早地降临了。雪积得有一英尺高,但是很快就融化了。雪后第二周乔捎话来叫他们下山,说是另一场更大的暴风雪正从太平洋往这边推进,他们收拾好东西,和羊群一起往山下走。石头在他们的脚边滚动,紫色的云团不断从天空西边涌来,风雪将至,空气中的金属味驱赶着他们不断前行。在从断云漏下的光影中,群山时隐时现。风刮过野草,穿过残破的高山矮曲林,抽打着岩石,发出野兽般的嘶吼。大山仿佛被施了法似的沸腾起来。下陡坡的时候,埃尼斯就像电影里的慢动作那样,头朝下结结实实地摔了一个跟头。

乔?安奎尔付了他们工钱,没说太多。不过他看过那些满地乱转的羊后,面露不悦:“这里头有些羊可没跟你们上山。”而羊的数量,也没有剩到他原先希望的那么多。农场的人干活永远不上心。

“你明年夏天还来吗?”在街上,杰克对埃尼斯说,一脚已经跨上了他那辆绿色卡车。寒风猛烈,冷得刺骨。“也许不了。”风卷起一阵灰尘,街道笼罩在迷雾阴霾之中。埃尼斯眯着眼睛抵挡着漫天飞舞的沙砾。“我说过,十二月我就要和阿尔玛结婚了,想在农场找点事做。你呢?”他的眼神从杰克的下巴移开,那里在最后一天被他一记重拳打得乌青。

“如果没有更好的差事,这个冬天我打算去我爹那儿,给他搭把手。要是一切顺利,春天的时候我也许会去德州。”“好吧,我想我们还会再见面的。”风吹起了街上的一只食物袋,一直滚到埃尼斯的车子底下。

“好。”杰克说,他们握手道别,在彼此肩上捶了一拳。两人渐行渐远,别无选择,唯有向着相反的方向各自上路。分手后的一英里,每走一码路,埃尼斯都觉得有人在他的肠子上掏了一下。他在路边停下车,在漫天席卷的雪花中,想吐但是什么都吐不出来。他从来没有这么难受过,这种情绪过了很久才平息下来。

十二月,埃尼斯和阿尔玛?比尔斯完婚,一月中旬,阿尔玛怀孕了。埃尼斯先后在几个农场打零工,后来去了沃什基郡罗斯特凯宾北部的老爱尔伍德西塔帕,当了一名牧马人。他在那一直干到九月份女儿出世,他把她叫做小阿尔玛。卧室里充斥着干涸的血迹味、乳臭味和婴儿的屎臭味,回荡着婴儿的哭叫声、吮吸声和阿尔玛迷迷糊糊的呻吟声。这一切都显示出一个和牲畜打交道的人顽强的生殖力,也象征着他生命的延续。

离开西塔帕后,他们搬到了瑞弗顿镇的一间小公寓里,楼下就是一家洗衣店。埃尼斯不情不愿地当了一名公路维修工。周末他在Rafter B干活,酬劳是可以把他的马放在那里。第二个女儿出生了,阿尔玛想留在镇上离诊所近一点,因为这孩子得了哮喘。

“埃尼斯,求你了,我们别再去那些偏僻的农场了,”阿尔玛说道,她坐在埃尼斯的腿上,一双纤细的、长满了雀斑的手环绕着他。“我们在镇上安家吧?”

“让我想想。”埃尼斯说着,双手偷偷地沿着她的衬衫袖子向上移,摸着她光滑的腋毛,然后把她放倒,十指一路摸到她的肋骨直至果冻般的乳房,绕过圆圆的小腹,膝盖,进入私处,最后来到北极或是赤道——就看你选择哪条航道了。在他的撩拨下,她开始打颤,想把他的手推开。他却把她翻过来,快速地把那事做了,这让她心生憎恶——他就是喜欢这个小公寓,因为可以随时离开。

断背山放牧之后的第四年夏天,六月份,埃尼斯收到了杰克?崔斯特的信,是一封存局候领邮件。伙计,这封信早就写了,希望你能收得到。听说你现在瑞弗顿。我24号要去那儿,我想我应该请你喝一杯,如果可以,给我电话。

回信地址是德州的切尔里德斯。埃尼斯写了回信,当然,随信附上了他在瑞弗顿的地址。

那天,早晨的时候还烈日炎炎,晴空万里。到了中午,云层就从西方堆积翻滚而来,空气变得潮湿闷热。因为不能确定杰克几点钟能到,埃尼斯便干脆请了一整天的假。他穿着自己最好的白底黑色宽条纹上衣,不时地来回踱步,一个劲儿朝布满灰白色尘埃的街道上张望。阿尔玛说,天实在太热了,要是能找到保姆帮忙带孩子,他们就可以请杰克去餐馆吃饭,而不是自己做饭。埃尼斯则回答他只想和杰克一起出去喝喝酒。杰克不是个爱下馆子的人,他说。脑海中浮现出那些搁在圆枕木上的冰凉的豆子罐头,还有从罐头里伸出来的脏兮兮的汤匙。

下午晚些时候,雷声开始隆隆轰鸣。那辆熟悉的绿色旧卡车驶入了埃尼斯的眼帘,杰克从车上跳出来,一巴掌把翘起来的车尾拍下去。埃尼斯象被一股热浪灼到了似的。他走出房间,站到了楼梯口,随手关上身后的房门。杰克一步两台阶地跨上来。他们紧紧抓住彼此的臂膀,狠狠地抱在一起,这一抱几乎令对方窒息。他们嘴里念叨着,混蛋,你这混蛋。然后,自然而然地,就象钥匙找对了锁孔,他们的嘴唇猛地合在了一处。杰克的虎牙出血了,帽子掉在了地上。他们的胡茬儿扎着彼此的脸,到处都是湿湿的唾液。这时,门开了。阿尔玛向外瞥了一眼,盯着埃尼斯扭曲的臂膀看了几秒,就又关上了门。他俩还在拥吻,胸膛,小腹和大腿紧贴在一起,互相踩着对方的脚趾,直到不能呼吸才放开。埃尼斯轻声地,柔情无限地叫着“小宝贝”——这是他对女儿们和马匹才会用到的称呼。

门又被推开了几英寸,阿尔玛出现在细窄的光带里。

他又能说些什么呢。阿尔玛,这是杰克?崔斯特,杰克,这是我妻子阿尔玛。他的胸腔涨得满满的,鼻子里都是杰克身上的味道。浓烈而熟悉的烟草味儿,汗香味儿,青草的淡淡甜味儿,还有那来自山中的凛冽寒气。“阿尔玛,”他说,“我和杰克四年没见了。”好像这能成为一个理由似的。他目不转睛地盯着她,暗自庆幸楼梯口的灯光昏暗不明。

“没错。”阿尔玛低声说,她什么都看到了。在她身后的房间里,一道闪电把窗子照得好象一条正在舞动的白床单,婴儿开始哇哇大哭。

“你有孩子了?”杰克说。他颤抖的手擦过埃尼斯的手,有一股电流在它们之间噼啪作响。

“两个小丫头。”埃尼斯说,“小阿尔玛和弗朗仙。我爱死她们了。”阿尔玛的嘴角扯了扯。

“我有一个男孩。”杰克说,“八个月大了。我在切尔德里斯娶了个小巧可爱的德州姑娘,叫露玲。”他们脚下的地板在颤动,埃尼斯能够感受到杰克哆嗦得有多么厉害。

“阿尔玛,我要和杰克出去喝一杯,今晚可能不回来了,我们想边喝边聊。”

“好。”阿尔玛说。从口袋里掏出一美元纸币。埃尼斯猜测她可能是想让自己带包烟,以便早点回来。“很高兴见到你。”杰克说。颤抖得像一匹精疲力尽的马。

“埃尼斯。”阿尔玛伤心地呼唤着。但是这并没能使埃尼斯放慢下楼梯的脚步。他应声道:“阿尔玛,你要想抽烟,就去卧室里我那间蓝色上衣的口袋里找。”

他们坐着杰克的卡车离开了,买了瓶威士忌。20分钟后就在西斯塔汽车旅馆的床上翻云覆雨起来。一阵冰雹砸在窗子上,随即冷雨接踵而至。风撞击着隔壁房间那不算结实的门,就这么撞了一夜。房间里充斥着精液、烟草、汗和威士忌的味道,还有旧地毯与干草的酸味,以及马鞍皮革,粪便和廉价香皂的混合怪味儿。埃尼斯呈大字型摊在床上,精疲力竭,大汗淋漓,仍在喘息,阴茎还半勃起着。杰克一面大口大口地抽烟,一面说道:“老天,只有跟你干才会这么爽。我们得谈谈。我对上帝发誓,我从来没指望咱们还能再在一起……好吧,我其实这么指望过,这就是我来这儿的原因,我早就知道会有这么一天。我真恨不得插上翅膀飞过来。”

“我不知道你到底去了什么鬼地方。四年了,我都要绝望了。我说,你是不是还在记恨我打你那一拳。”“伙计。”杰克说,“我去了德克萨斯州,在那儿碰见了露玲。你看那椅子上的东西。”在肮脏的桔红色椅背上,安尼斯看到一条闪闪发光的牛仔皮带扣。“你现在驯牛啦?”

“是啊,有一年我才赚了他妈的三千多块钱,差点儿饿死。除了牙刷什么都跟人借过。我几乎走遍了德州每一个角落,大部分时间都躺在那该死的货车下面修车。不过我一刻也没想过放弃。露玲?她是有几个钱,不过都在她老爹手里,用来做农业机械用具生意,他可不会给她一个子儿,而且他挺讨厌我的。能熬到现在真不易……”

“你可以干点儿别的啊。你没去参军?”粼粼雷声从遥远的东边传来,又挟着红色的冠形闪电离他们而去。

“他们不会要我的。我椎骨给压碎过,肩胛骨也骨折过,喏,就这儿。当了驯牛的就得随时准备被挑断大腿。伤痛没完没了,就像个难缠的婊子。我的一条腿算是废了,有三处伤。是头公牛干的。它从天而降,把我顶起来,然后摔出去八丈远,接着开始猛追我,那家伙,跑得真他妈快。幸亏有个朋友把油泼在了牛角上。我浑身零零碎碎都是伤,肋骨断过,韧带裂过。我爹那个时代已经一去不复返了。要发财得先去上大学,或者当运动员。像我这样的,想赚点小钱只能去驯牛。要是我玩儿砸了,露玲她爹一分钱都不会给我的。想清楚这一点,我就不指望那些不切实际的理想了。我得趁我还能走路出来闯闯。”

埃尼斯把杰克的手拉到自己的嘴边,就着他手里的香烟吸了一口,又吐出来。“我过得也是跟你差不多的鬼日子……你知道吗,我总是呆坐着,琢磨自个儿到底是不是……我知道我不是。我的意思是,咱俩都有老婆孩子,对吧?我喜欢和女人干,但是,老天,那是另外一回事儿。我从来没有想过和一个男人干这事儿,可我手淫的时候总在没完没了地想着你。你跟别的男人干过吗?杰克?”

“见鬼,当然没有!”杰克说。“你瞧,断背山给咱俩的好时光还没有走到尽头,我们得想法子走下去。”“那年夏天,”埃尼斯说,“我们拿到工钱各分东西后,我肚子绞痛得厉害,一直想吐。我还以为自己在迪布瓦餐厅吃了什么不干净的东西。过了一年我才明白,我是受不了身边没有你。认识到这一点真是太迟、太迟了。” “伙计,”杰克说。“既然这样,我们必须得弄清楚下一步该干什么。”

“恐怕我们什么也干不了。”埃尼斯道。“听说我,杰克。我已经过了这么多年这样的生活,我爱我的丫头们。阿尔玛?错不在她。你在德州也有妻有儿。就算时光倒流,咱们还是不能正大光明地在一起,”他朝自己公寓的方向甩了甩脑袋,“我们会被抓住。一步走错,必死无疑。一想到这个,我就害怕得要尿裤子。”

“伙计,那年夏天可能有人看见咱们了。第二年六月我曾经回过断背山——我一直想回去的,却匆匆忙忙去了德州——乔?安奎尔在他办公室对我说了一番话。他说:小子,你们在山上那会儿可找到乐子磨时间了,是吧?我看了他一眼。离开的时候,发现他车子的后视镜上挂着一副比屁股蛋子还大的望远镜。”

其实,还有些事情,杰克没告诉埃尼斯:当时,乔斜靠在那把嘎嘎作响的木头摇椅上,对他说:“崔斯特,你们根本不该得酬劳,因为你们胡搞的时候让狗看着羊群。”并且拒绝再雇佣他。他继续说道:“是的,你那一拳真让我吃惊,我怎么也想不到你会打得这么狠。”

“我上面还有个哥哥K?E,比我大三岁。这蠢货每天都打我。我爹真烦透了我总是哭哭啼啼的。我六岁的时候,爹让我坐好,对我说:埃尼斯,有麻烦,要么解决,要么忍受,一直忍到死。我说,可他比我块儿头大呀。我爹说,你趁他不注意的时候偷偷动手,揍疼他就跑,甭等他反应过来。我依计行事。把他弄进茅坑里,或者从楼梯跳到他身上,晚上他睡觉的时候把枕头拿走,往他身上粘脏东西……这么折腾了两天之后,K?E再也不敢欺负我了。这件事儿的教训就是,遇上事儿,废话少说,赶快搞定。”

隔壁电话铃响了起来,一直响个不停,越来越高亢,接着又嘎然停止。

“哼,你甭想再打到我。”杰克说。“听着,我在想,如果我们可以在一起开个小农场,养几头母牛和小牛,还有你的马,那日子该有多滋润。我跟你说,我再也不去驯牛了,我再也不干那断老二的活儿了,我可不想把骨头都给拆散了。听见我的计划了吗,埃尼斯,就咱俩。露玲他爹肯定会给我钱,多多少少会给点……”

“不不不,这不是个好法子,我们不能那么干。我有自己的生活轨道,我不想捅娄子。我也不想变成我们有时候会看到的那种人。我不想死。以前,我们家附近有两个人——厄尔和瑞奇——开了爿农场。爸爸每次经过都要对他俩侧目而视。他们是所有人的笑柄,尽管俩人都又英俊又结实。我九岁的时候,他们发现厄尔死在灌溉渠里。是被人用轮胎撬棍打死的,他们拖着他的鸡巴满世界转,直到把那玩意儿给扯断了。他全身血肉模糊的,像一摊西红柿,鼻子都被打得稀巴烂。”

“你看见啦?”“我爹让我看的,他带我去看的。我和K?E。我爹笑个不停。老天,他要是还活着,看见咱们这样,也会拿棍子把咱俩整死!两个男人一起过?不,我觉得咱俩倒是可以过段时间聚一次……“多久一次?”杰克说。“他妈的四年一次怎么样?”

“不,”埃尼斯说。忍着不去争辩。“我他妈的想起你明天早晨就得走而我得回去工作就生气。但是,碰上麻烦,要么解决,要么忍受。操!我经常看着街上的人问自己,别人会这样吗?他们会怎么做?”

“在咱们俄怀明不能有这种事,要是真发生了,我不知道他们会怎么做,也许去丹佛。”杰克说。他坐起来,转过身。“我不想怎么着,操,埃尼斯,就几天。我们离开这,立刻走,把你的东西扔到我的后车厢,咱们动身到山里去。给阿尔玛打电话告诉她你要走了。来吧,埃尼斯,你刚把我干得够呛,现在你得补偿我。来吧,不会出事儿的。

隔壁房间那空洞的电话铃再度响起,好像要应答它似的,埃尼斯拿起桌边的电话,拨通了家里的号码。

埃尼斯和阿尔玛之间,有什么东西正在慢慢腐烂。并没什么真正的矛盾,但距离却越来越远。阿尔玛在杂货店当店员。她不得不出来工作,这才能把埃尼斯赚的钱存下来。阿尔玛希望埃尼斯用避孕套,因为她怕再怀孕。但是他拒绝了,说你要是不想再给我生孩子我就不要你了。她小声嘟囔:“你要是能养得起我就生。”心里却在想,你喜欢干的那事儿可生不出孩子来。

她心里的怨怼与日俱增:她无意中瞥见的那个拥抱;他每年都会和杰克?崔斯特出去两三回,却从不带她和孩子们度假;他不爱出门也不爱玩儿;他老是找些报酬低,耗时长的粗重活干;他喜欢挨墙睡,一沾床就开始打呼;他就是没办法在县城或电力公司找份长期的体面差事;他使她的生活陷入了一个无底黑洞……于是,在小阿尔玛9岁,弗朗仙7岁的时候,她和埃尼斯离婚,嫁给了杂货店老板。

埃尼斯重操旧业,这个农场干干,那个农场呆呆,没挣多少钱,不过倒是挺自在。想干就干,不想干就辞职,到山里呆上一阵子。他只有一点点被背叛的感觉,不过也不是很在意。每次跟阿尔玛和她的杂货店老板以及孩子们一起过感恩节,他都会表现出轻松的样子。坐在孩子们中间,讲马儿的故事,说说笑话,尽量不显得像个失意老爹。

吃过馅饼后,阿尔玛把他打发到厨房里,一边刷盘子一边说自己担心他,说他应该考虑再婚。他看到她怀孕了。大约四五个月了,他估计。

“一朝被蛇咬,十年怕井绳。”他斜靠着柜橱说,觉得这房间好小。

“你现在还跟杰克?崔斯特出去钓鱼吗?”

“有时候会去。”他觉得她要把盘子上的花纹都擦掉了。

“你知道么?”她说。从她的声音里,他预感到有些不对劲。“我以前老是奇怪,你怎么从来没带一条半条鲑鱼回来过,你总是说你抓了好多啊。于是,在你又要出去钓鱼的前一天晚上,我打开了你的鱼篮子。五年前的价格签还在那儿挂着呢。我用绳子绑了根纸条系在篮子里。上面是这么写的:嗨,埃尼斯,带些鱼回来。爱你的阿尔玛。后来你回来了,说你们抓了一堆鱼,然后吃了个精光,记得不?我后来找了个机会打开篮子,看见那张纸条还绑在那儿,绳子连水都没沾过。”仿佛为了配合“水”这个词的发音似的,她拧开水龙头,冲洗着盘子。

“这也证明不了什么嘛。”

“别扯谎了,别把我当傻子,埃尼斯。我知道那是怎么回事儿。杰克?崔斯特是吧?都是那个下流的杰克,你跟他……”

她戳到了他的痛处,他一把抓住她的手腕。她的眼泪痛得涌出来,盘子掉在地上摔个粉碎。

“闭嘴!”他说,“管好你自己的事儿吧,你根本什么都不明白!”

“我要喊比尔了!”

“随你的便,你尽管喊啊。我要让他在地板上吃屎,还有你!”他猛地又一扭,她的手腕立刻火烧火燎地痛起来。他把帽子向后一推然后重重甩上了门。那天晚上他去了黑蓝鹰酒吧,通宵买醉,还狠狠打了一小架。

之后很长时间,他都没有去看自己的女儿。他想过几年她们就能明白他的感受了。

他们都已不再青春年少。杰克的肩膀和屁股上都堆满了肉。埃尼斯还像晾衣竿儿那么瘦,一年四季穿着破靴子、牛仔裤和衬衫,只有在天冷的时候才会加一件帆布外套。岁月使他的眼皮儿都耷拉下来,断过又接好了的鼻梁弯得像只钩子。

年复一年,他们跨越高原,穿过峡谷,在崇山峻岭之间策马放牧。从大角山到药弓山,从加勒廷山南端到阿布萨罗卡斯山,从花冈山到夜枭湾, 还有桥梁般的特顿山脉。他们的足迹直至佛瑞兹奥特山、费雷斯山、响尾蛇山和盐河山脉。他们还曾两度造访风河山。还有马德雷山脉、范特雷山、沃什基山、拉腊米山——但是再也不曾回过断背山。

后来,杰克的德州岳父死了。露玲接手了她爹的农牧机械生意,开始展示出经商的手腕儿。杰克稀里糊涂地挂了个经理的头衔,成日价在牲口和机械展销会之间晃荡来晃荡去。他有了些钱,不过都杂七杂八地花掉了。说话也带上了点儿德州口音,比如把“母牛”说成“木牛”,把“老婆”说成“捞婆”。他将前面的大牙给磨平了,镶了镶,倒也没多疼。还留上了厚厚的唇髭。

1983年5月,他们在几处结冰的高山湖泊边过了几天冷日子。接着便打算穿过黑耳斯图河。

一路前行。天气虽然晴好,水流却湍急幽深,岸边的湿地泥泞难走。他们辟出一条狭窄的道路,赶着马穿过了一片小树林。杰克的旧帽子上还插着那根鹰羽。他在正午的烈日下抬起头,嗅着空气里的树脂芬芳,还有干树叶和热石头的气味儿。马蹄过处,苦刺柏纷纷歪倒零落。埃尼斯用他那饱经风霜的眼睛向西了望,但见一团浓云将至未至。头上的青天依然湛蓝深邃,就像杰克说的,他都要淹死在这一片蔚蓝之中了。

大约三点钟,他们穿过一条羊肠小道,来到了东南面的山坡上。此处春日正暖,冰雪渐消。流水潺潺,奔向远方。二十分钟之后,他们被一头觅食的黑熊给吓了一跳。那熊朝他们滚过来一根圆枕木,杰克的马惊得连连后退,暴跳如雷。杰克喝道:“吁……”又拉又拽的费了好半天劲儿。埃尼斯的马也是又踏又踩又打响鼻儿,不过好歹还算镇定。黑熊倒给吓坏了,一路狂奔逃进森林。步履沉重,地动山摇。

茶褐色的河水,带着融化的积雪,汇成一股急流,撞击在山石上,溅起朵朵水花,形成漩涡逆流。河堤上杨柳微动,柳絮轻飏,好似漫天飞舞的淡黄色花瓣。杰克跳下马背,让马饮水。自己则掬起一捧冰水,晶莹的水滴从他指间滑落,溅湿了他的嘴唇和下巴,闪闪发亮。

“别那么做,会发烧的。”埃尼斯说道。接着又说:“真是个好地方啊。”河岸上有几座陈旧的狩猎帐篷,点缀着一两处篝火。河岸后面隆起一面草坡,草坡四周黑松环绕,地上还有一些干木头。他们默不做声地安营扎寨,然后把马牵到坡上去吃草。杰克打开一瓶威士忌,喝了一大口,又深深吐了口气,说道:“威士忌正是我两件宝贝之一。”然后把瓶子盖好,抛给了埃尼斯。

到了第三天,不出埃尼斯所料,那块雨云果然挟着风,夹着雪片,灰蒙蒙地从西面涌来。过了一个小时,风雪渐缓,化作了温柔的春雪,空气变得潮湿而厚重。夜更深更冷了,他们上上下下地搓着自己的关节,篝火彻夜不灭。杰克骂骂咧咧地诅咒着天气,拿根棍子翻动着火堆,一个劲儿地换台,直到把收音机折腾得没了电。

埃尼斯说他和一个在狼耳酒吧打零工的女人搞上了——他如今在西格诺给斯图特埃米尔干活——不过也没什么结果,因为那女的有的地方不太招他待见;杰克则说他近来和切尔德里斯公路边上一家牧场的老板娘有一腿。他估计总有那么一天,露玲或者那戴绿帽子的老公会宰了他。埃尼斯轻轻笑骂道“活该”。杰克又说他一切都还好,就是有时候想埃尼斯想得发疯便忍不住要拿起鞭子抽人。

马儿在暗夜的火光中嘶鸣。埃尼斯伸臂搂住杰克,把他拥进怀里。他说他大概一个月见一次女儿,小阿尔玛17岁了,腼腆害臊,长得跟他似的又瘦又高,弗朗仙则是个疯丫头。杰克把冰凉的手搁在埃尼斯大腿中间,说担心自家儿子有阅读障碍什么的,都已经十五岁了,什么都不会念。露玲硬是不承认,非说孩子没事儿——有钱顶个屁用。

“我曾经想要个小子,”埃尼斯边说边解开纽扣,“没想到上天注定是岳父命。”

“我儿子闺女都不想要,”杰克说,“操!这辈子我想要的偏偏都得不到。”他说着把一截朽木扔进了火堆里,火星子和他们那些絮絮叨叨的废话情话一起四下里飞溅,落在他们的手上、脸上。就这样,他们又一次滚倒在脏兮兮的土地上。这么多年以来,在他们屈指可数的几次幽会当中,有一点从来不曾改变:那就是时间总是过得太快,总是不够用,总是这样。

一两天之后,在山道的起点处,马匹都被赶上了卡车。埃尼斯要动身回西格诺去了,杰克则要回赖特宁平原看他爹。埃尼斯靠着车窗,对杰克说:他已经把回程推迟了一周,得等到十一月份冬牧期开始之前,牲口们都被运走之后,他才能再次出来。

“十一月?!那八月呢?咱们不是说好了八月份抽个十来天在一起的?老天爷,埃尼斯,你为什么不早点说,你他妈的一个礼拜屁都不放一个!为什么我们非得挑那种冻死人的鬼天气啊?不能这样下去了,干吗不去南方?我们可以去墨西哥啊。”

“墨西哥?杰克,你知道的,我不能去那么远的地儿。我八月一整月都得打包,这才是八月份该干的事。听着,杰克,咱们可以十一月去打猎,逮它一头大麋鹿。我看看还能不能借到罗尔先生那个小屋子,咱们那年在那儿多开心。”

“嘿,伙计,我可他妈的开心不起来。老是说来就来说走就走,你以为你是谁?”

“杰克,我得工作——以前我倒是可以拍拍屁股就走人。你有个有钱的老婆,有份好工作,你已经忘记当穷光蛋的滋味儿了。你知道养孩子有多难吗?这么多年来我不知道花了多少钱,以后还得花更多。让我跟你说,我不能扔掉这个饭碗。而且那时候我真走不开,母牛要产仔,且有得忙呢。斯图特埃米尔很麻烦,他因为我要迟回去一星期可没少为难我。我不怪他,我走后他连个囫囵觉都甭想睡。我跟他讲好了,八月份我不走——你能说出什么更好的法子来吗?”

“我从前说过。”杰克的声音苦涩,带着抱怨。

埃尼斯默然不语,缓缓站直身子,轻轻摸了摸自己的额头。一只马在车上跺脚。他走向自己的卡车,把手放在车厢上,说了些只有马儿才能听见的话,接着慢慢地走回来。

“你去过墨西哥了,杰克?”墨西哥那种地方他听说过,他要打破砂锅问到底,弄个水落石出。

“去过怎么着,有他妈的什么问题吗?”这个话题时隔多年又再度被提起,有点儿迟,也有点儿突然。“我总有一天得跟你说说这事儿,杰克,我可不是傻瓜。我现在是不知道你干了什么,”埃尼斯说,“等我知道了你就死定了。”

“来啊,你倒是试试看,”杰克说,“我现在就能跟你说:我们本来可以一起过上好日子,那种真正的好日子。但你不肯,埃尼斯,所以我们有的只是一座断背山,全部的寄托都在断背山。小子,要是你以为还有别的什么,那我告诉你,这就是他妈的全部!数数二十年来我们在一起的日子,看看你是怎么象拴狗一样拴住我的。你现在来问我墨西哥,还要因为你想要干又不敢干的事儿杀了我?你不知道我过得多糟糕!我可不是你,我不愿意一年一两次在这种见鬼的高山上偷偷摸摸地干。我受够了,埃尼斯,你这个该死的狗娘养的,我真希望我知道怎么才能离开你!”

就象是冬天里突然迸发的热气流,这么多年来他们之间从不曾说出口的感受——名分,公开,耻辱,罪恶,害怕……统统涌上心头。埃尼斯的心被狠狠地击中了。他面如死灰,表情扭曲,闭上了眼睛。双拳紧握,两腿一软,重重地跪在地上。

“天啊,”杰克叫道,“埃尼斯?”他跳下卡车,想看看埃尼斯是心脏病犯了还是给气坏了。埃尼斯却站起身,像个衣架子似的,直挺挺地向后退去。他爬上卡车,关上车门,又蜷缩了起来——他们仍旧是在原地打转,没有开始,没有结束,也没有解决任何问题。

让杰克?崔斯特一直念念不忘却又茫然不解的,是那年夏天在断背山上埃尼斯给他的那个拥抱。当时他走到他身后,把他拉进怀里,充满了无言的、与性爱无关的喜悦。

当日,他们在篝火前静立良久,红彤彤的火焰摇曳着,把他俩的影子投在石头上,浑然一体,宛如石柱。只听得埃尼斯口袋里的怀表滴答作响,只见火堆里的木头渐渐燃成木炭。在交相辉映的星光与火光中,埃尼斯的呼吸平静而绵长,嘴里轻轻哼着什么。杰克靠在他的怀里,听着那稳定有力的心跳。这心跳仿佛一道微弱的电流,令他似梦非梦,如痴如醉。直到埃尼斯用从前母亲对自己说话时常用的那种轻柔语调叫醒了他:“我得走了,牛仔。你站着睡觉的样子好像一匹马。”说着摇了摇他,便消失在黑暗之中。杰克只听到他颤抖着说了声“明儿见”,然后就听到了马儿打响鼻的声音和马蹄得得远去之声。

这个慵懒的拥抱凝固为他们分离岁月中的甜蜜回忆,定格为他们艰难生活中的永恒一刻,朴实无华,由衷喜悦。即使后来,他意识到,埃尼斯不再因为他是杰克就与他深深相拥,这段回忆、这一刻仍然无法抹去。又或许,他是明白了他们之间不可能走得更远……无所谓了,都无所谓了。

埃尼斯一直都不知道杰克出了意外,直到数月之后,他寄给杰克的明信片被盖上“收件人已故”的戳记退了回来。于是他拨通了杰克在切尔德里斯的号码——这号码他只打过一次,那还是在和阿尔玛离婚之前。当时杰克误会了他的意思,驱车120英里匆匆赶来却一无所获。

没事儿的,杰克一定会听电话,他必须听——但是杰克并没有,接电话的是露玲。当他问起杰克的死因时,露玲说当时卡车轮胎突然爆裂,爆炸的碎片扎进了杰克的脸,撞碎了他的鼻子和下巴,把他砸晕了过去。等到有人发现时,他已经死在了血泊之中。

不,埃尼斯想,他肯定也是给人用棍子打死的。

“杰克常提起你,”她说。“你是他钓鱼的伙伴还是打猎的伙伴来着?你瞧,我不太清楚你的姓名和住址。杰克总喜欢把他朋友的地址记在脑袋里——出了这种事儿真可怕,他才39岁。”

巨大的悲伤如北方平原般笼罩住了他。他不知道这究竟怎么回事儿,到底是意外还是人为。血卡在杰克的嗓子里,却没人帮他翻一翻身。在狂风的低吼中,他仿佛听到钢铁刺穿骨头的声音,看到轮胎的金属圈砸碎了杰克的脸。

“他埋在哪儿?”他真想破口大骂:这娘们儿就让杰克死在了那样一条土路上。

那细细的德州口音从电话里传来:“我们给他立了块碑。他曾经说过死后要火化,然后把骨灰撒在断背山上,我也不知道那是什么地方。按照他的愿望,我们火葬了他。我留下了一半骨灰,另一半给了他家人,他们应该知道断背山在哪。但是,你也知道杰克,断背山大概只是他凭空想象的地方,一个蓝知更鸟声声吟唱,威士忌畅饮不衰的地方。”

“有一年夏天,我们在那里放羊。”埃尼斯几乎说不出话来。

“哦,他总说那是他的地盘。我还以为他是喝醉了,威士忌喝多了。他经常喝。”

“他的家人还住在赖特宁平原么?”

“是的,他们生生世世都住在那里。我从没见过他们,他们也没来参加葬礼。你要是能联系他们,我想他们会很高兴帮助杰克完成遗愿。”

她无疑是彬彬有礼的,但那细细的声音却冷如冰霜。

去赖特宁平原的路上要经过一座孤零零的村庄,每隔8到10英里就能看到一处荒凉的牧场,房子伫立在空荡荡的草堆中,篱笆东倒西歪。其中一个信箱上写着:约翰?C?崔斯特。农场小得可怜,杂草丛生。牲口离得太远,他看不清楚它们长得怎么样,只觉得都黑乎乎、光秃秃的。一条走廊,一幢褐色的泥房子,四个房间,上层两间,下层两间。

埃尼斯和杰克的老爹坐在厨房的餐桌旁。杰克的母亲,身形矮胖,步履蹒跚,好像刚做完手术。她说:“喝杯咖啡吧?要不吃块樱桃蛋糕?”

“谢谢,夫人。我要杯咖啡就好,我现在吃不下蛋糕。”

杰克他爹却一直闷声不响地坐着,双手交叠放在塑料桌布上,怒气冲冲地盯着埃尼斯,一副“我什么都知道”的模样。他相貌寻常,长得像池塘里的大头鹅。他从这两位老人身上找不到半丝杰克的影子,只好深深地叹了口气。

“对杰克的事,我难过极了……说不出的伤心。我认识他很久了。我来是希望你们能让我把杰克的骨灰带到断背山。杰克的太太说这是他的愿望。如果你们同意,我很乐意代劳。”

一片沉默。埃尼斯清了清嗓子,但什么也没说。

老爹开口了。他说:“我跟你说,我知道断背山在哪儿。他大概也知道自己不配埋在祖坟里。”

杰克的母亲仿佛没听到这话,说,“他每年都回来,即使结了婚又在德州安了家也还是那样,他一回来就帮他爹干活,整个星期都在忙,修大门啊,收庄稼啊,什么都干。我一直保留着他的房间,跟他还是个小男孩那会儿一模一样。要是你愿意,可以去他房间看看。”

那老爹生气地接口:“我看没必要。杰克老是念叨 ‘埃尼斯?德?玛尔’,还说‘我总有一天会把他带来,我们一起打理爹的农场’。他还有好多好多半生不熟的主意,都是关于你俩的。盖个小屋,经营农场,赚大钱……今年春天他带回另外一个人来,说是他在德州的邻居。他还说要和他那德州老婆分手回这儿来呢。反正他那些计划没一个实现的。”

埃尼斯现在知道了,杰克一准儿是给人打死的。他站起来,说‘我一定得看看杰克的房间’,说这话的同时想起了杰克和他爹之间的一件往事:杰克的阴茎是弯的,但他爹不是。这种生理上的不一致让做儿子的很是困扰。有那么三五次,杰克在厕所里待着不出来,解开裤子纽扣,估量着马桶和那玩意儿的位置,结果尿得满地都是。这可把他爹气坏了,简直是勃然大怒(杰克当时回忆说):“老天爷,他差点儿宰了我。把我往洗澡盆上撞,用皮带抽我,对我大吼:你想知道尿了一地是啥滋味吗?让我来告诉你!接着他就把那东西抽出来朝我身上尿,淋了我满头满脸。然后扔了块毛巾给我,让我擦干净地,又命令我把衣服脱了洗干净,还有毛巾,也得洗干净。从那时起,我突然发现我跟他不一样,那种不一样,就像缺了只耳朵或者烫了个烙印一样明显。从那之后,他就没再正眼看过我。”

陡峭蜿蜒的楼梯把埃尼斯带进了杰克的卧室。房间又小又热,下午的阳光从西窗倾泻进来,把一张窄小的男孩床逼进墙角。一张墨迹斑斑的桌子,一把木椅子,一杆双筒熗挂在床头手工制作的熗架上。窗外,一条碎石路向南延伸,他蓦然想起,杰克小时候就只认得这一条路。床边贴着一些从旧杂志上剪下来的照片,照片上那些黑头发的电影明星,都已经褪色发黄。埃尼斯听到杰克的妈妈在楼下烧开水、灌满水壶、又把它放回炉子,同时在和杰克的老爹小声儿嘀咕。

卧室里的衣橱,其实就是一个浅浅的凹槽,架着根木棍。一条褪色的布帘子把它跟整个房间隔离开来。衣柜里挂着牛仔裤,仔细烫过,并且折出笔直的裤线。地上放着双似曾相识的破靴子。衣橱最里面,挂着一件衬衣。他把衣服从钉子上摘下来,认出那是杰克在断背山时曾穿过的。袖子上已经干涸的血迹却是埃尼斯的——在断背山上的最后一天,他们扭打的时候,杰克用膝盖磕到了埃尼斯的鼻子,血流得他们两个身上都是,大概也流在了杰克的袖子上。但埃尼斯不能肯定,因为他还用它包过折断翅膀的野鸽子。

那衬衣很重。他这才发现里面还套着另外一件,袖子被仔细地塞在外面这件的袖子里。那是埃尼斯的一件格子衬衣,他一直以为是洗衣店给弄丢了。他的脏衬衣,口袋歪斜,扣子也不全,却被杰克偷了来,珍藏于此。

两件衬衣,就象两层皮肤,一件套着另一件,合二为一。他把脸深深埋进衣服纤维里,慢慢地呼吸着其中的味道,指望能够寻觅到那淡淡的烟草味,那来自大山的气息,以及杰克身上独特的汗香。然而,气味已经消散,唯有记忆长存。断背山的绵绵山峦之间,有一种无形的力量——它什么都没留给他,却永远在他心底。

最终大头鹅老爹也不肯把杰克的骨灰给他:“告诉你,他得埋在自家的祖坟里。”杰克的妈妈用削皮器削着苹果,对他说:“你可得再来啊。”

回去的路上,埃尼斯颠簸着经过村里的墓地。那只不过是一小块林间空地,松松垮垮地围着栅栏。有几座墓前搁着塑料假花。埃尼斯不知道杰克的墓是哪一座,不知道他被埋在这片伤心平原的哪个角落。

几个星期后的一个周六,他把斯图特埃米尔家那些脏毯子扔上卡车,拉到洗车处,用高压水熗冲洗。在工人们将洗干净的湿毯子往车上搬的空当儿,他走进了辛吉斯礼品店,开始忙着挑选明信片。

“埃尼斯,你这是找什么呢?”玲达?辛吉斯问他,顺手把用过的咖啡滤纸扔进了垃圾筒。

“断背山的风景明信片。"

“在弗里蒙特的那座?”

“不是,北面那座。”

“我没进这种明信片,不过我可以把它列在进货单上,下次给你进上一百张,反正我也得进点儿明信片。”“一张就够。”

明信片到了,三十美分。他把它贴在自己车里,四个角用黄铜大头钉钉住。又在下面敲了跟铁钉,拿铁丝衣架把杰克和他的衬衣挂了起来。他后退几步,端详着套在一起的两件衬衣,泪水夺眶而出,刺痛了他的双眼。

“杰克,我发誓……”他说。尽管杰克从没要求过他发什么誓,杰克自己就不是一个会发誓的人。

从那时起,杰克开始出现在他的梦里。还像初次见面时那样,头发卷曲,微笑着,露出虎牙。他也有梦到那些放在枕木上的豆子罐头和从罐头里伸出来的汤匙柄。形状象卡通画,颜色也很怪异,使他的梦境显得又滑稽又色情。汤匙柄还会变成轮胎撬棍……一觉醒来,他有时伤心,有时高兴。伤心的时候枕头会湿,高兴的时候床单会湿……

他知道发生了什么事,却无法相信它。到如今已经回天乏力,于事无补,只好默默承受。

|